Microbiota gut-brain axis in Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Overview

By Pr. Premysl Bercik

Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, Hamilton, Canada

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Author

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, is the most common functional gastrointestinal disorder and is frequently accompanied by psychiatric comorbidities. Its pathophysiology is not fully understood but impairment in the gut-brain communication seems to underlie its genesis, with microbiota playing an important role in this process. Microbiota composition and its metabolic activity differ between patients with IBS and healthy controls, but no specific profiles have been identified. However, transplantation of fecal microbiota from IBS patients into germ-free mice induces gut dysfunction, immune activation and altered behavior in the murine host, similar to those observed in patients, thus suggesting its causal role. Furthermore, treatment with antibiotics or probiotics improve symptoms in some patients with IBS. Better understanding of the microbial-host interactions that lead to gut symptoms and psychiatric comorbidities, as well as discovery of new biomarkers that identify those who may benefit from microbiota directed treatments, are needed for optimized management of patients with IBS.

62% of respondents thought that consuming probiotics helped to maintain healthy microbiota balance and function

Irritable bowel syndrome

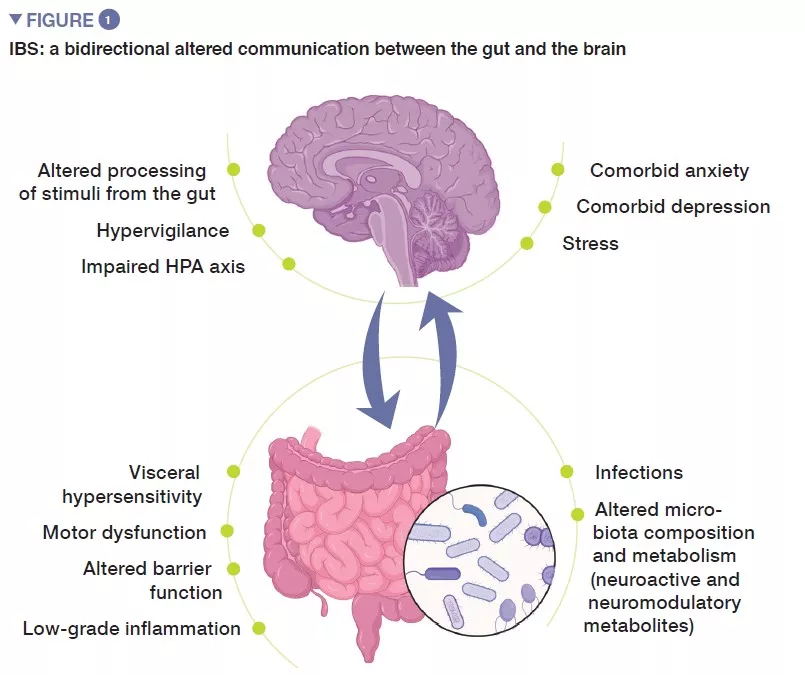

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, that is associated with changes in stool frequency or stool form, in the absence of any organic disorder. Using ROME IV criteria, IBS is classified into four subtypes: IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C), IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D), with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M) or IBS, unsubtyped (IBS-U) which does not meet the criteria for IBS-C, D, or M [1]. Psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression and somatization are common in patients with IBS (Figure 1).

Although IBS prevalence rates appear to differ between countries, it is estimated to affect around 1 in 10 people globally [2]. IBS can develop at any age, but its onset is often usually between age of 20 and 30. Women are almost twice as likely as men to have symptoms of IBS, they also report to feel more fatigue and psychiatric comorbidities. The quality of life of IBS patients is severely affected, interfering with their everyday life, frequently resulting in missing work or school. The economic burden of IBS on healthcare systems and society is significant, with both direct and indirect costs. Mean annual direct cost for IBS patients was calculated at 1363 Euros, in addition to patients missing on average 8-22 days of their work per year.

Pathophysiology of IBS is not fully understood, but in general it stems from impaired gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication between the digestive tract and the central nervous system. It likely involves multiple underlying mechanisms, including peripheral factors, such as visceral hypersensitivity, altered motility, increased intestinal permeability and low-grade inflammation. Among central factors, altered processing of signals from the gut, hypervigilance, stress, as well as psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, seem to play an important role. During the last decade, increasing attention has been given to gut microbiota as a key player in IBS.

Key facts

- IBS is characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits.

- Its prevalence is around 11%, predominantly affecting women, it has a significant socio-economic impact.

- Its pathophysiology is not fully understood, it is considered to be a disorder of the gut-brain interaction.

Microbiome in Irritable Bowel Syndrome

There are several lines of evidence, both from clinical studies and animal models, that implicate gut microbiota in IBS. First, bacterial gastroenteritis is the strongest risk factor for IBS, with 11-14% of patients developing chronic symptoms after acute infection with Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli or Clostridioides difficile infection [3]. Clinical data suggest that female sex, younger age, severity of infection and preceding psychiatric morbidity are risk factors for IBS. In addition, variants in genes related to the gut permeability, recognition of bacteria and innate immune responses have been identified.

Second line of evidence comes from clinical studies that demonstrated that certain antibiotics may improve symptoms in a proportion of patients with IBS [4]. On the other hand, clinical data also suggest that use of antibiotics, with likely subsequent intestinal dysbiosis, can lead to symptoms generation. And finally, multiple clinical trials have suggested that specific probiotics improve symptoms of IBS, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea or bloating.

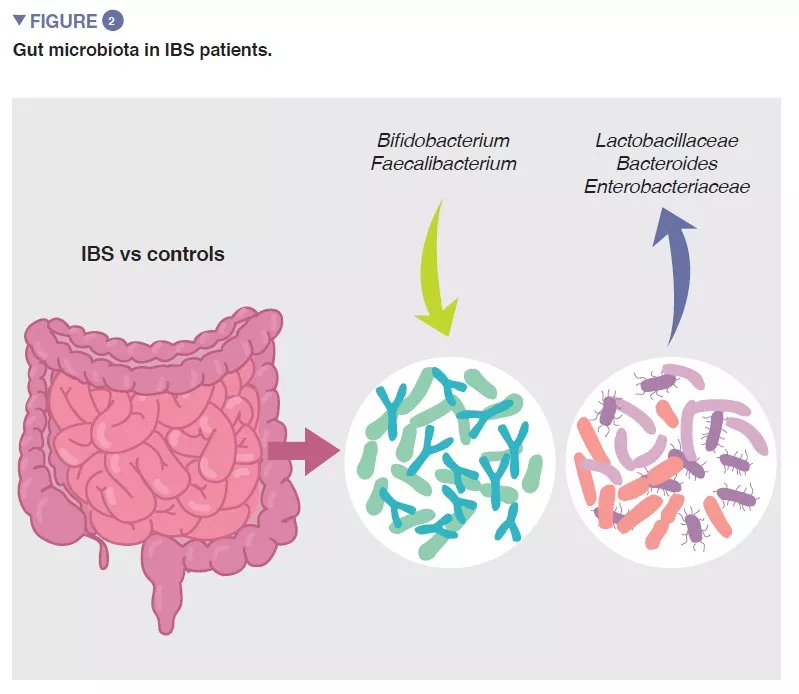

The bacterial population thriving in the gut, collectively termed the gut microbiota is one of the major determinants of gut homeostasis. Accumulating data show that gut microbial composition and its metabolic activity differ between IBS patients and healthy controls, and that they associate with intestinal symptoms, as well as with anxiety and depression. However, the results from individual studies are highly variable and there seems to be no unique microbial profile that could be attributed to IBS. Despite this, a recent meta-analysis identified several microbial features, including increase in family Enterobacteriaceae, family Lactobacillaceae, and genus Bacteroides and decrease in uncultured Clostridiales, genus Faecalibacterium, and genus Bifidobacterium in patients with IBS compared to healthy controls (Figure 2) [5]. There are also multiple bacterial or host-microbial metabolites that are altered in patient with IBS, including phosphatidylcholine, dopamine, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, bile acids, tryptamine and histamine metabolites. However, all these findings are suggestive of association but not of causation.

The microbiota humanized mouse model is a valuable tool to establish the causal role of the gut microbiota in the IBS, and to study the underlying mechanisms leading to gut dysfunction. We used stool microbiota from patients with IBS-D and from age- and sex-matched healthy controls to colonize germ-free mice and studied them 4 weeks later. Mice colonized with IBS-D microbiota developed faster gastrointestinal transit, changes in gut barrier function and lowgrade intestinal inflammation, compared to mice colonized with microbiota from healthy controls [6]. Furthermore, mice that were colonized with microbiota from patients with comorbid anxiety also developed anxiety-like behavior, suggesting that microbiome transplantation from IBS patients into the murine host not only alters the gut function, but also impairs the gutbrain communication. These functional abbehanormalities

were associated with changes in multiple neuro-immune gene networks, as well as changes in many microbial and host metabolites. Interestingly, treatment with a probiotic normalized gastrointestinal transit and anxiety-like behavior in mice with IBS-D microbiota, which was associated with changes in microbiota profiles and bacterial indole production, reaffirming the notion that the gut microbiome plays a key role in the gut-brain communication [7].

Key facts

- Bacterial gastroenteritis is the most significant risk factor for IBS.

- Microbiota-directed treatment (antibiotics, probiotics) can improve IBS symptoms.

- Microbiota profiles and metabolism differ in patients with IBS and healthy controls.

- Microbiota transplantation from IBS patients into germ-free mice can induce gut and brain dysfunction.

Microbiota-gut-brain axis

The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system between the gut and the brain integrated via neural, hormonal, and immunological signalling. Growing evidence suggests that the gut microbiota plays a key role in the communication between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system, with most data being obtained from animal studies [8]. Germ-free mice have abnormal behavior, associated with changes in expression of multiple genes and chemistry in the brain, altered blood-brain barrier, changes in morphology of brain regions involved in control of mood and anxiety (amygdala and hippocampus), altered myelination profile and plasticity, as well as global defects in brain microglia. Most of these abnormalities are normalized after bacterial colonization. Microbiota also modifies behavior in conventional mice, as administration of non-absorbable antimicrobials can increase their exploratory behavior, together with changes in Brain- Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus and amygdala. Changes in behavior induced by antibiotics have been also described in patients treated for acute infections or during eradication of chronic Helicobacter pylori infection; this condition was coined “antibiotic-induced psychosis”. Interestingly, a recent large population- based study found that use of antibiotics in early childhood was associated with an increased risk of developing mental health disorders in later life.

However, the most obvious case for the microbiota-gut-brain axis comes from patients with cirrhosis-associated hepatic encephalopathy that manifest with changes in behavior, mood and cognition [9]. These patients show dramatic improvement in brain function after administration of antibiotics or laxatives, and recent studies suggested that similar amelioration can be also achieved by fecal microbiota transplantation.

During recent years, multiple studies investigated gut microbiome in patients with psychiatric disorders, such as major depression and generalized anxiety, and found that the microbial profiles differed between patients and healthy controls. Furthermore, transferring microbiota from patients into germ-free or antibiotic treated rodents induced anxiety and depressive-like behanormalities viors. This raises question whether those probiotics, which showed beneficial effects on behavior and brain chemistry in animal models, could be used to treat patients with psychiatric diseases. The results of the few studies completed so far suggest that probiotics, if used as an adjunctive treatment, might improve symptoms in some patients with major depressive disorder [10].

We conducted a pilot RCT study in patients with IBS and comorbid depression to assess effects of a probiotic that showed beneficial effects on behavior and brain chemistry in several mouse models [11]. We found that compared to placebo, a 6-week probiotic treatment improved depression scores and overall symptoms of IBS. This was associated with changes in neuronal activation in the amygdala and other brain regions involved in mood control, as assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. This suggest that some probiotics may produce neuroactive metabolites that could be harnessed not only for treatment of patients with functional bowel disorders, but also for those with mental health issues. However, more rigorous clinical studies are needed to confirm and validate these findings.

Key facts

- Gut microbiota modifies behavior, as well as brain chemistry and structure in animal models.

- Clinical data suggest that microbiome is involved in cognition and mood disorders, such as hepatic encephalopathy, major depression and generalized anxiety.

- Specific probiotics might improve depressive behavior in patients, but more clinical data are needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusion

Irritable bowel syndrome is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder with frequent psychiatric comorbidities, that negatively affects patients quality of life and has significant socio-economic impact. Its pathophysiology is not fully understood, but it is likely multifactorial and is considered to be a disorder of the gut-brain interaction. Gut microbiota appears to play a key role in IBS, possibly through interactions with the immune or neural system, although the exact underlying mechanisms have to be clarified. Gut bacteria have the capacity to affect behavior and brain structure, and some probiotics might be beneficial for treatment of both gut and brain dysfunction.

1 Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016: 150: 1393-407.

2 Black CJ, Ford AC. Global burden of irritable bowel syndrome: trends, predictions and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 17: 473-86.

3 Barbara G, Grover M,Bercik P, et al. Rome Foundation Working Team Report on Post-Infection Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2019; 156: 46-58.

4 Ford AC, Harris LA, Lacey BE, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48: 1044-60.

5 Pittayanon R, Lau JT, Yuan Y, et al. Gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome - a systematic review. Gastroenterology 2019; 157: 97-108.

6 De Palma G, Lynch MD, Lu J, et al. Transplantation of fecal microbiota from patients with irritable bowel syndrome alters gut function and behavior in recipient mice. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9: eaaf6397.

7 Constante M, De Palma G, Lu J, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 modulates the microbiota-gut-brain axis in a humanized mouse model of irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021; 33: e13985.

8 Morais LH, Schreiber HL, 4th, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021; 19: 241-55.

9 Acharya C, Bajaj JS. Chronic liver diseases and the microbiome-translating our knowledge of gut microbiota to management of chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology 2021; 160: 556-72.

10 Nikolova VL, Cleare AJ, Young AH, Stone JM. Updated review and meta-analysis of probiotics for the treatment of clinical depression: adjunctive vs. stand-alone treatment. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 647.

11 Pinto-Sanchez MI, Hall GB, Ghajar K, et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression scores and alters brain activity: a pilot study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2017; 153: 448-59.