When diet and microbiota influence endometriosis

A mouse model has highlighted a link between diet, gut health, and endometriosis. A Western diet doubles the size of endometriosis lesions, modifies metabolism and immunity, and alters the gut microbiota of rodents.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

“Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food”: this saying often attributed to Hippocrates could easily apply to patients with endometriosis, a disease which affects 10% of women of childbearing age.

Some say a less inflammatory diet (rich in vegetables and fruit, low in fat, etc.) can reduce the pain associated with endometriosis. Conversely, could the Western diet – low in fiber and high in fat – exacerbate the disease? Apparently so, says a team 1 which studied the disease in a murine model.

10% Endometriosis affects roughly 10% (190 million) of reproductive age women and girls globally. ²

Lesions twice as large

Eight-week-old mice were fed either a control diet (17% fat) or a diet mimicking the Western diet (45% fat, low fiber) for four weeks. The researchers induced endometriosis in the mice by surgical means, then used ultrasound to monitor the development of their lesions for seven weeks, before sacrificing the mice to analyze the lesions.

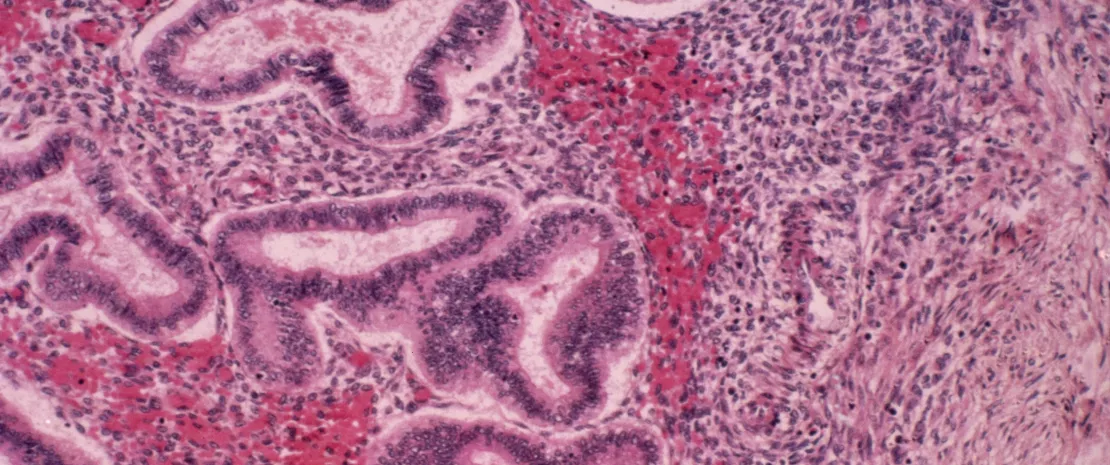

The result? The mice on a Western diet developed lesions twice as large as those on the control diet. In addition, their lesions exhibited greater fibrosis and cell proliferation.

Metabolic and immune alterations

At the same time, metabolic and immune alterations were observed. In conclusion, the Western diet:

- exacerbates macrophage activity in the lesions;

- activates the leptin pathway, which is involved in cell migration and invasion and is known for its influence on glucose metabolism;

- and increases glucose oxidation, which is involved in the growth of lesions.

This led the authors to suggest a “metabolic” hypothesis: endometriosis alters the gut barrier function, allowing toxic bacterial metabolites to leak into circulation. The result is low-grade inflammation and a vicious circle whereby leptin promotes the invasion, implantation, and growth of endometrial cells, with their growth in turn fueled by increased glucose metabolism.

Depletion of A. muciniphila

A study of the mice’s gut microbiota also showed that the induction of endometriosis modified gut microbiota composition, regardless of diet.

In the mice on a Western diet, endometriosis induction reduced or even eliminated Akkermansia muciniphila, often considered anti-inflammatory. This depletion may go hand in hand with the increased macrophage activity observed in the lesions.

However, these initial results are limited to mice. Further in-depth research will be required to untangle the complex interaction between gut microbiota and endometriosis, define optimal diets for endometriosis patients, and evaluate the effects of a healthier diet.