The interaction between the oral microbiota and SARS-COV-2 infection

Overview

By Dr. Jay Patel

Usher Institute of Population Health Sciences and Informatics, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

The mouth accommodates a high and diverse bacterial load embedded within extracellular matrices. Poor oral hygiene encourages dysbiotic shifts in these polymicrobial biofilms, fostering increasingly pathogenic bacterial species to colonise and proliferate. While the microbiota is known to mediate inflammation, recent studies suggest that dysbiosis of the oral microbiota could be associated with the severity and duration of Covid-19 symptoms. For these patients, maintaining or enhancing oral hygiene practices may improve clinical outcomes.

A HISTORY OF VICIOUS PARTNERSHIP

Viral infections are known to precipitate bacterial co-infections. The majority of deaths in the 1918 influenza pandemic were directly attributable to secondary bacterial pneumonia [1]. Furthermore, severe clinical outcomes during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic were associated with bacterial co-infections [2]. The challenge of viral-bacterial copathogenesis during infectious disease outbreaks can significantly complicate the global response, retard recovery, and accelerate antimicrobial resistance. Fortunately, findings from a multicentre cohort study of nearly 50,000 patients revealed that few bacterial infections were reported in patients hospitalised with Covid-19 [3]. However, it should be noted that diagnosing co-infections is complex, as the organisms might present prior to the viral infection; as part of an underlying chronic infection; or may be contracted nosocomially [4].

THE ORAL MICROBIOTA: FROM EUBIOSIS TO DYSBIOSIS

The oral cavity and upper respiratory tract harbour a high and richly diverse bacterial load. In health, the oral microbiome maintains a finely-tuned, harmonious relationship but small changes in routine behaviours can cause substantial ecological shifts in this symbiosis. Poor oral hygiene can render the environment pathogenic, transitioning the microbiome into a state of dysbiosis, where the conditions for disease processes are enhanced [5, 6].

Periodontal disease – chronic inflammation of the gingiva (gums) – is primarily mediated by the inflammatory components within the biofilm and alters the architecture of the gingival tissues to present micro-ulcers. These form a communication between the oral cavity and the blood, which leads to routine activities (e.g. chewing, flossing, and tooth brushing) inducing bacteraemia. Oral bacteria and inflammatory mediators are then disseminated widely via the blood, reaching vital organ systems. Evidence shows that exposure to bacteraemia can be significantly damaging and contributes to a low-grade systemic inflammation precipitating inflammatory conditions [5]. Moreover, periodontitis is known to be an aggravating factor in the incidence of type II diabetes and oral microbiota dysbiosis is involved in both periodontal and metabolic disorders (cardiovascular diseases, dyslipidaemia…) [7].

ORAL DYSBIOSIS AND COVID-19 SEVERITY, IS THERE A LINK?

Research on this association is limited, but the few studies that do exist point towards intriguing connections. A double-blinded cross-sectional study of 303 PCR-confirmed Covid-19 patients in Egypt investigated the interplay between three factors: 1) oral hygiene; 2) the severity of Covid-19; and 3) the C-reactive protein (CRP) values. CRP is a marker of hyper-inflammation, hence patients with high levels of CRP were hypothesised to have a poorer prognosis with COVID-19 [8]. The researchers found that poor oral health was correlated to increased values of CRP and delayed recovery period.

A (unmatched) case-control study of 568 patients in Qatar found that periodontitis was associated with severe COVID- 19 complications, including a 3.5 times increase in the need for a ventilator; a 4.5 times increase in the risk of intensive care admission; and an 8.8 times increase in the risk of death [9]. Although these results do not suggest causality and other factors may be implicated, the associations are stark and warrant further questions around the true role of oral dysbiosis on Covid-19 outcomes.

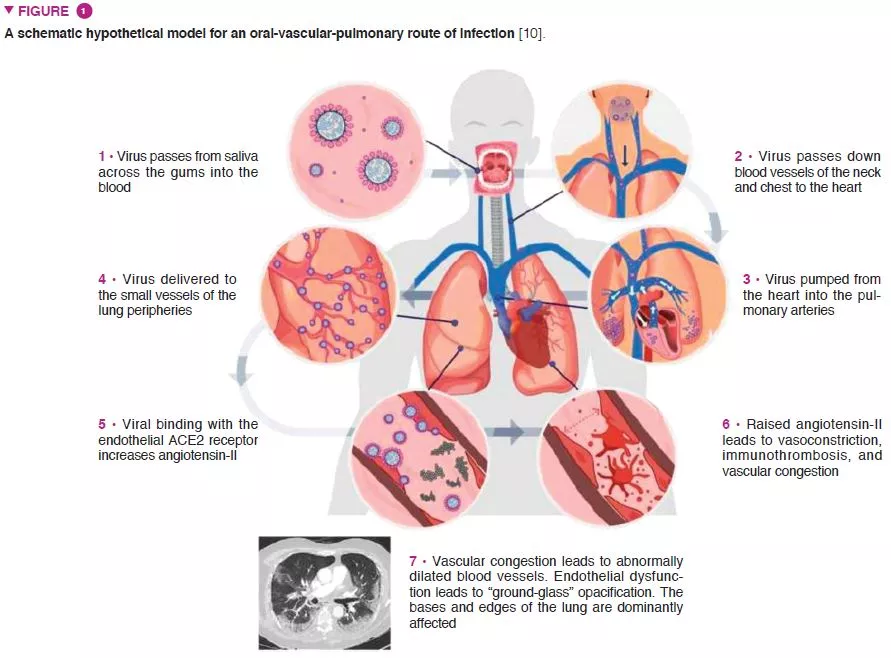

This largely hypothesised relationship is based on a number of factors that have shared relevance in the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection and periodontitis. For instance, pulmonary radiological evidence of primary vascular pathological processes suggests an oral-vascular- pulmonary axis forming a direct route of infection, in addition to direct vascular delivery to the pulmonary vessels (Figure 1) [10]. Secondly, metagenomic analyses have determined that the upper respiratory tract – a key initial anatomical site of infection – is high in bacterial species implicated in oral diseases, and the role of the oral cavity as a natural viral reservoir. Thirdly, adequate viral survival within the sub-gingival biofilm and the ability for viral translocation from saliva to the periodontal pocket – both contributing towards an evasion of the host immune response. Fourthly, the abundance of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors on key components of the oral-vascular-pulmonary axis.

GOOD ORAL HYGIENE

Regardless of the precise nature of oral microorganisms implicated in the pathophysiology of Covid-19, good oral hygiene should be encouraged for the known benefits to oral and general health. Scrupulous toothbrushing twice daily, interdental cleaning and use of an adjunctive mouthwash are relatively simple measures that will disturb the biofilm, maintain a symbiotic flora and decrease the salivary viral concentration.

Conclusion

In summary, the role of poor oral hygiene on the severity of Covid-19 outcomes is understudied and unclear. However, the potential role for a clinically-relevant interplay logically follows. Maintaining or improving oral hygiene practices has clear benefits on oral and general health and during SARS-CoV-2 infections may also improve the prognosis of the disease.