Highlights from the 54th Espghan

CONGRESS REVIEW

By Pr. Koen Huysentruyt

Pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, Brussels Centre for Intestinal Rehabilitation in Children (BCIRC), Belgium

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

The 54th annual ESPGHAN meeting was held from the 22 to the 25th of June 2022 in the beautiful city of Copenhagen. It was the first time that the meeting took place again in real life after two years of limitations due to the Covid pandemic. It was a great opportunity to meet with experts in paediatric gastro-enterology, hepatology and nutrition from all over the world to share knowledge, research and interesting new insights. The aim of this article is to highlight a few of the topics addressed about the microbiome.

THE VIROME

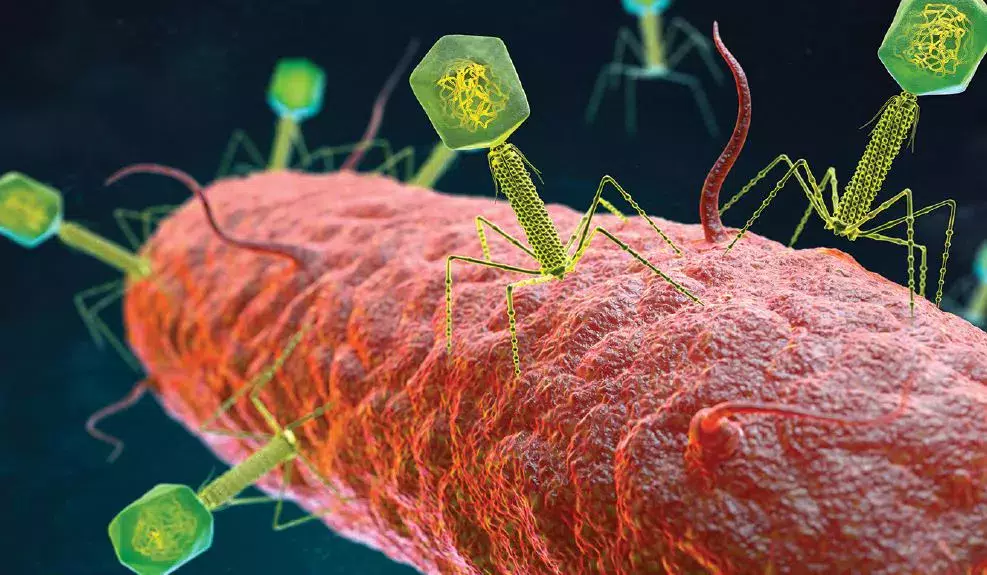

Pr. Dennis Sandris Nielsen introduced us to the virome, a collection of viruses that we carry, which is an emergent research field that appears to play an important role in human health and disease. Faecal sample analysis shows that approximately 6% of the found DNA is not of bacterial, but of viral origin. For every bacteria in the human body, a virus matches it. Like the microbiome, the virome is influenced by pre-, peri- and postnatal factors (diet, environment, siblings, medication, etc.). Those viruses are thus omnipresent in the gut and play a key role in the regulation of the gut microbiome. Bacteriophages are a type of viruses that attack bacteria in a host specific matter. Two different types of interactions are described: “kill-the-winner dynamics” and “piggyback-the-winner dynamics”. In the first, the bacteriophages attack the bacteria, inject its DNA and use the bacteria as a host to create new phage particles after the cell is lysed. The speaker makes an analogy with lions and gazelles in the Savannah, meaning constant-diversity dynamics, destruction of niche competitors, phage shunt and bacterial turnover and pressure on host for diversification of the phage receptor. In the latter, the virus rides with the winner, by integrating its DNA in the genome of the bacteria, altering the host cell and making it more efficient, thus making the winner a winner. A study on faecal samples of a healthy infant population in Denmark identified more than a 10.000 viral species, belonging to 248 viral families. Remarkably, 232 of those families were not previously described, supporting the hypothesis that only the tip of the iceberg has yet been discovered [1]. The questions that are raised is what implication it has on human health, and if it plays a role in immune system maturation. Gut virome imbalance might play a role in disease development (i.e. VEO-IBD, NEC, etc.).

C-SECTION AND MICROBIOME

The mode of delivery at birth plays a key-role in the early shaping of the gut microbiome. Babies that are born vaginally are exposed to different bacterial strains compared to those delivered by C-section, with different colonization as a consequence. In addition, the reason for a C-section is more than often due to a foetal emergency. Those babies are more likely to have a low pH on cord blood, which causes a reduction in tight junction permeability promoting dysbiosis.

Breastfeeding seems to counteract the deleterious effect of C-section on the microbiota and remains the golden standard in infant nutrition. However, women who deliver by C-section are less likely to breastfeed, or delay breastfeed initiation, and infants are then formula fed. For this reason, researchers are constantly looking for the perfect cocktail of pre-, pro-, syn- or postbiotics to mimic the gut microbiome of a breastfed infant.

Dr Eduardo López-Huertas discussed a strain of Lactobacillus fermentum and showed promising results in infants delivered by C-section. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), they analysed the stool samples of infants fed with a symbiotic formula containing L. fermentum and GOS and found major resemblances to the samples of breastfed infants (higher bifidobacteria, lower faecal pH) [2]. Furthermore, it is shown in a recent meta-analysis (3 trials) that L. fermentum reduces the incidence of gastrointestinal infections with 73% in C-section born infants. More research is needed to investigate possible advantages in potential disease prevention, i.e., gastrointestinal tract or respiratory tract infections, especially in C-section born babies, that have a disadvantageous gut microbiome [3].

HMOS IN INFANT FORMULA AND THE MICROBIOME

Dr. Giles Major provided us with his insights in the link between glycans and the gut microbiome. Glycans or human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) affect the overall gut microbiome composition. Mother milk consists of many different HMOs that vary in concentration in breastmilk depending on the ethnicity of the mother and during the infant’s growth. When the gut microbiome at an early age is investigated, we notice a predominance of bifidobacteria in breastfed compared to formula fed infants. These bifidobacteria are important as they take up carbon and produce short-chain fatty acids that modulate the gut barrier permeability. Their carbon-source are HMOs, and the microbiome plays a role in the digestion of those HMOs trough the presence of CAZymes. Thus, the CAZymes you have, will determine which glycans you can digest and the type of glycans a child is fed will steer the microbiome maturation trough early-life.

A RCT is conducted where a control group of formula fed infants was compared to test groups who received a 5-HMO-Blend formula. The trial is still ongoing, but preliminary results show that the overall gut microbial diversity was significantly different in the control group compared to the test group, where in the test group the composition became more similar to the breastfed infants. The speaker suggests this could be the consequence of promotion of bifidobacteria, although this was just a speculation.