Immunotherapy coupled with FMT in patients with refractory melanoma: a Phase I trial

According to a phase I trial on 20 patients, anti-PD-1 immunotherapy coupled with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) induces no more adverse effects than immunotherapy alone, with responses potentially improved.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

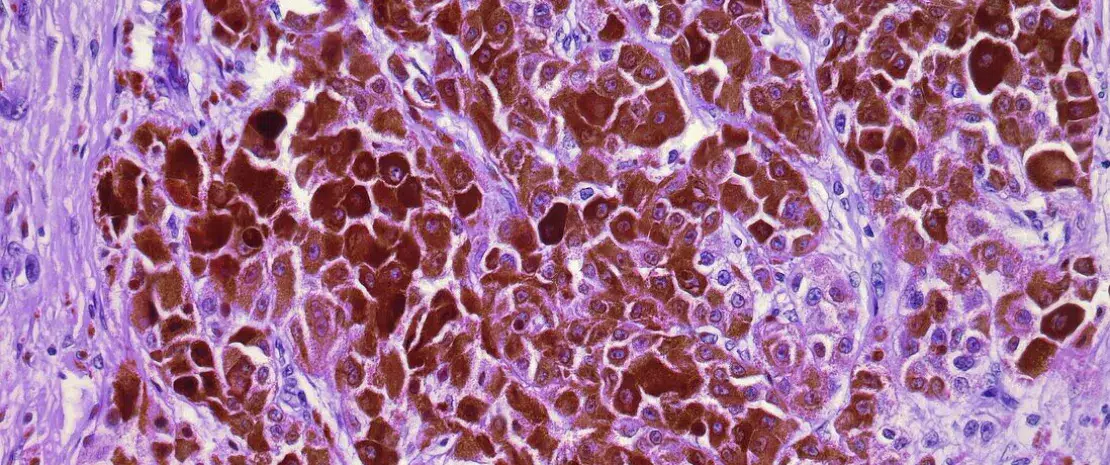

Over the past decade, the therapeutic arsenal available to treat advanced melanoma has grown. Despite this, half of patients receive no benefit from anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Combination therapy using (sidenote: Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy based on immune checkpoint inhibitors that target the PD-1 checkpoint, reversing the deactivation by the tumor of the recognition system associated with the PD-1 protein present on the surface of T lymphocytes. The immune system’s effectiveness against tumor cells is thus restored. ) and (sidenote: Anti-CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibitor that targets the CTLA-4 checkpoint ) improves response rates, but is associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs). The gut microbiota regulates the immune system. So what about combining anti-PD-1 with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)? This option was explored in a multicenter phase I trial involving (sidenote: aged 48 to 90 (average age of 75.5 years), including 12 men (60%) ) with unresectable or metastatic melanoma who had not previously received anti-PD-1 treatment. They received oral FMT (capsules) from a (sidenote: three healthy male donors (average age of 35 years) provided the feces used for 4, 7, and 9 patients, respectively ) , followed seven days later by a first cycle of (sidenote: nivolumab or pembrolizumab ) .

Comparable safety

The trial’s primary endpoint was safety. FMT induced at most grade 1 or 2 adverse events (diarrhea, flatulence, etc.) in 8 patients (40%). Following anti-PD-1, 17 patients (85%) showed side effects, including 5 patients (25%) with grade 3 irAEs (2 arthritis, 1 fatigue, 1 pneumonia, 1 nephritis) which required temporary discontinuation of treatment. Compared with anti-PD-1 alone (79.5%-93.2% irAEs in phase III clinical trials, including 13.3%-34.0% grade 3-5 irAEs), combined treatment with FMT and anti-PD-1 did not increase the incidence of these events.

Potentially improved response

In terms of efficacy, the objective response rate of 65% (13 patients) was satisfactory and higher than that of anti-PD-1 alone (54%-63% in randomized phase III trials), although the small sample size and absence of a control group (anti-PD-1 only) limit interpretation of the results. The respective donor had no apparent effect on the outcome.

Long-term changes in gut microbiota

(sidenote: at baseline, immediately before anti-PD-1, then 1 month and 3 months after anti-PD-1 ) shows that the diversity of recipients’ gut microbiota only increases after FMT. In terms of composition, one week after FMT, the microbiota of all recipients more closely resembled those of their respective donors. However, this similarity subsequently regressed in future non-responders but increased in responders.

One month after FMT, the flora of responders was enriched in (sidenote: Ruminococcus, Eubacterium ramuleus, and Faecalibacterium ) and depleted in (sidenote: Clostridium methylpentosum, Enterocloster aldensis, Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum, and Enterocloster clostridioformis ) .

An effect on T lymphocytes?

The study also showed changes in patients’ plasma metabolites, with an increase in primary and secondary bile acids. After FMT, certain T lymphocytes (ICOS+CD8+) increased in the peripheral blood of responders only.

Lastly, mouse models treated with antibiotics prior to FMT confirm the role of FMT in increasing anti-PD-1 efficacy.