Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) efficacy: the right dose of bacteria

The gut microbiota is thought to modulate the efficacy of certain anti-cancer drugs such as ICIs. Now it is being studied in the search for bacteria that predict the efficacy of this treatment. However, the results are not quite as expected.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

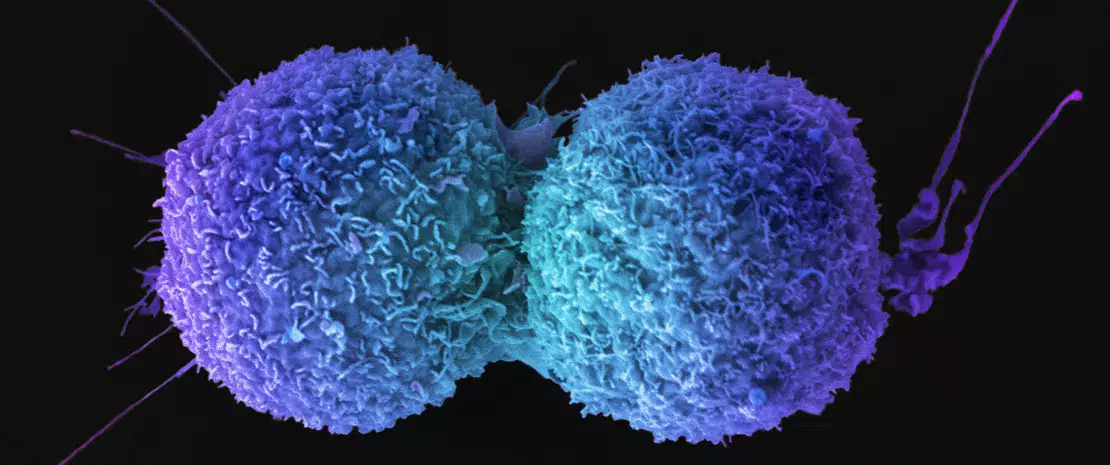

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) represent a major breakthrough in the treatment of certain cancers, offering patients an overall survival superior to that expected with chemotherapy, notably in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and melanoma. However, some patients do not respond to this treatment as hoped. This difference may be linked in part to the gut microbiota, which is thought to influence the effectiveness of ICIs.

This topic has been the subject of numerous studies, several of which have recently been published in Nature Medicine. The results have improved our understanding in this area, while showing that the mechanisms involved are more complex than initially believed.

Akk in lung cancer: neither too little nor too much

A first retrospective multicenter study analyzed the microbiota of 338 French patients with advanced NSCLC. The aim was to predict a positive clinical response to anti-PD-1, a type of ICI treatment. More specifically, the investigators sought to confirm previous results obtained in smaller cohorts suggesting that the composition of the gut microbiota, and more specifically the presence of the bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila (Akk), could serve as a biomarker of response and survival at twelve months.

The results? The relative abundance of Akk was clearly associated with clinical benefit (better response rate, better survival). Moreover, the presence of Akk in the gut was an indicator of the richness of the intestinal ecosystem. It was associated with a specific bacterial community linked to health or immunogenic status, represented by Ruminococcacae and Lachnospiraceae, as well as B. adolescentis and I. butyriciproducens.

However, good survival rates require the right abundance of Akk, neither too little nor too much. Indeed, antibiotic use (20% of cases) favored an overabundance of Akk and of the genus Clostridium, both of which are associated with resistance to ICI and an unfavorable outcome (reduced survival). Thus, it appears that antibiotic-induced dysbiosis reduces beneficial bacteria associated with survival (such as Ruminococcus), in favor of harmful bacteria associated with immunoregulatory or pro-inflammatory pathways (such as Escherichia coli and Clostridium bolteae). Therefore, the relative abundance of Akk represents a potential biomarker (favorable or unfavorable) to refine the stratification of NSCLC patients receiving anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. It may even provide a way of improving responses to treatment via Akk supplementation.

Relationships more complex than expected

A second study based on five previously published cohorts (n = 147) and five new cohorts (n = 165) confirmed that the gut microbiome is associated with response to ICIs and survival in advanced melanoma. However, this association was found to be cohort dependent. In other words, each cohort had its own signature. Consequently, no single species could be regarded as a fully consistent biomarker across studies. Instead, a panel of species, including Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum, Roseburia spp., and Akk., may serve as such.

Thus, this second study confirms what the first study suggested: the role of the human gut microbiota in responses to ICI is more complex than previously thought. Neither the presence or absence of any single bacterial species, nor the abundance thereof, as with Akk., is sufficient to define responders or non-responders to ICI treatment.

This has major implications for future research, namely the need to use larger sample sizes and to take into account the complex interaction of clinical factors (such as antibiotics) with the gut microbiota during treatment.

Recommended by our community

"Gut #Microbiome is a fascinating area of new knowledge we should be aware of!" - Linga Fruit Winery (From Biocodex Microbiota Institute on X)