Expert interview: Pr. Brigitte Dréno

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that appears in periodic flareups. Like asthma, hay fever or allergic conjunctivitis, it is classified as an allergic disease. The disease causes very poorly defined oozing red lesions to appear in specific locations on the skin, such as in the folds of the elbow or behind the knees, but at times also on the face or the rest of the body. AD usually appears in early childhood, and may persist into adulthood. The causes are multifactorial and complex and include a genetic predisposition (mutation of the skin protein, filaggrin), an alteration of the skin barrier, a dysbiosis of the skin and gut microbiota, and immune dysregulation.

AD affects 15%-20% of children and 10% of adults in “developed” countries. The number of cases has increased significantly in recent decades due to pollution and contact with allergens.1

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Author

What factors cause flare-ups ?

Inflammatory outbreaks can be triggered by multiple factors, including stress, pollution, cold, humidity, certain allergens (pollen), certain medications, woolen clothing, and certain cosmetics containing plants or essential oils.

The causes of atopic dermatitis are multifactorial and complex and include a genetic predisposition, an alteration of the skin barrier, a dysbiosis of the skin and gut microbiota, and immune dysregulation.

What do we know about the links between atopic dermatitis, the microbiota and immunity?

On a pathophysiological level, AD is characterized by an alteration of the skin barrier, a skin and gut dysbiosis, and immune dysregulation with the activation of Th2 lymphocytes. This immune dysregulation leads to a major cytokine surge, which in turn causes the inflammatory reactions.2

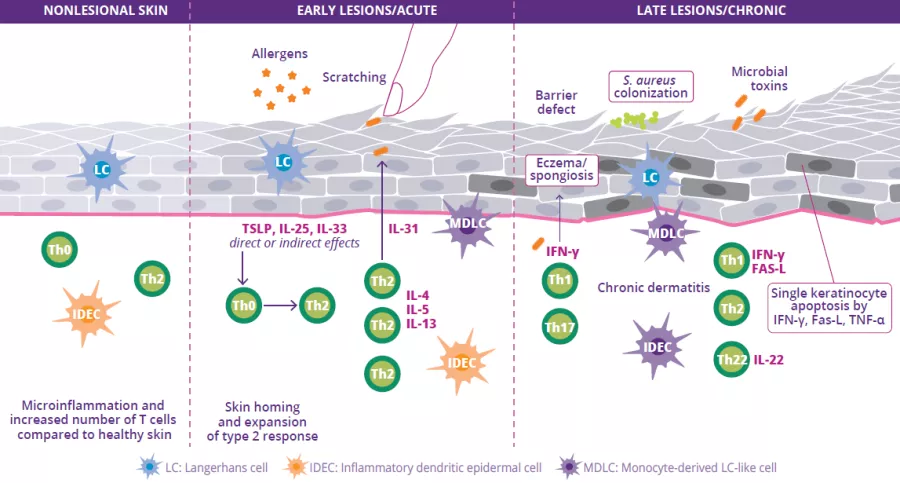

An alteration of the skin barrier is the starting point for a dysbiosis of the skin microbiota characterized by a reduction in bacterial diversity and the proliferation of Staphylococcus aureus. Allergen penetration leads to the activation of keratinocytes and the production of interleukin (IL-33, IL-25, TSLP), resulting in the differentiation of Th2 lymphocytes. These in turn secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13) characteristic of Type 2 inflammation (Fig 9). These cytokines directly activate the sensory nerves, provoking pruritus.

With chronic lesions, the skin barrier repairs itself poorly and becomes thicker, since it is subject to chronic inflammation. There is also a progressive increase in cytokines and Th cells (Th1, Th2, Th22) which secrete cytokines that contribute to the destruction of keratinocytes. Lastly, a gut dysbiosis may play a role in the disease’s pathophysiological mechanism.3

FIGURE 9: Pathogenesis, main mechanisms and pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis.

Adapted from Sugita K et al, 20204

What have recent discoveries about the microbiota taught you? Has your practice changed?

Recent discoveries about the microbiota have led me to better understand the importance of maintaining and repairing the skin barrier to control inflammation. As a systemic treatment, I advise my patients to use a cleansing gel that preserves the skin’s pH (pH ~5, avoid products with a basic pH), as well as a moisturizer and tailored cosmetic products. The findings also help us to better understand the skin’s immunological system and how to respect the skin’s microbiota.

The immune dysregulation in atopic dermatits leads to a major cytokine surge, which in turn causes the inflammatory reactions.2

What are your thoughts on the use of probiotics to treat AD or prevent relapse?

There are many ways to rebalance the skin microbiota in case of AD (probiotics, prebiotics, symbiotics, etc.)5 but the postbiotic approach seems to me the most interesting. Postbiotics are preparations of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host.6 They can restore the skin barrier via an anti-inflammatory action that allows bacteria to recolonize, therefore having a long-term impact on the microbiota. Oral probiotics or prebiotics are another interesting approach to regulating the intestinal system, which itself plays a general immunomodulatory role in the immune system.7