Oral microbiota and chronic conditions

By Dr. Jay Patel

Usher Institute of Population Health Sciences and Informatics, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Although the co-evolutionary role of the human microbiome as a determinant of human health is increasingly recognised in modern medicine, the oral microbiome remains a largely siloed factor contributing to general health and well-being. In health, the oral microbiome maintains a careful symbiotic equilibrium with the host, with harmful bacteria at clinically inconsequential levels. However, external environmental pressures readily turn the oral microbiome dysbiotic, where an improper proportional and diversity of microbes colonise the mouth. These environmental pressures are often highly modifiable risk factors. An expanding body of evidence suggests that the relevance of this disturbance is not merely confined to local disease activity but has a disseminated risk profile for other major chronic diseases of the body, with a high global burden of disease including diabetes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and rheumatoid arthritis.

In health, the oral microbiome represents a carefully balanced, diverse community protecting the mouth from disease. Modern lifestyle choices can readily upset this balance, rendering the community less protective and increasingly harmful.

Mechanism

The morphology, warmth and moisture of the mouth affords the oral microbiota a highly diverse habitat for colonisation and growth. From birth, children acquire a simple oral microbiome, and with age, the eruption of teeth, and the additive role of external factors, this community becomes increasingly complex. Both host-derived and microbially-derived factors maintain the homeostatic equilibrium of the oral microbiome required for health.

Poor oral hygiene can be a profound ecological pressure that steers complex microbial communities in the mouth into dysbiosis [1].

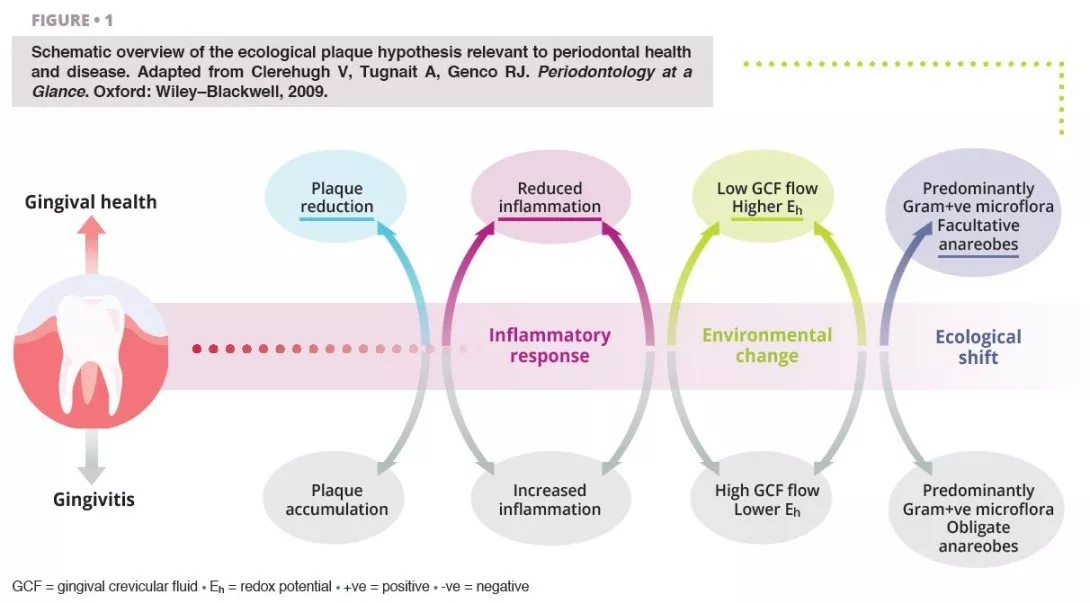

Ecological shifts in a dysbiotic ecosystem favour the colonisation and proliferation of pathogenic oral bacteria (figure 1). When these species increase in quantity, the risk of oral disease significantly increases. Periodontal disease is a chronic, non-resolving, inflammatory process leading to tissue breakdown of the tooth-supporting apparatus, and can lead to tooth loss, if untreated. Routine activities including chewing, flossing, and toothbrushing can induce bacteraemia, which facilitate haematogenous dissemination of oral bacteria and inflammatory mediators, inducing systemic inflammation in some patients [2]. Patients with periodontal disease––the sixth most prevalent condition affecting humankind globally [3]––show micro-ulcerated sulcular epithelia and damaged periodontal tissues, and thus seem more susceptible to bacteraemia. Therefore, the inflammatory state from periodontal disease metastasises to other sites of the body, which can occur at clinically-relevant levels. Good oral hygiene is therefore essential for controlling the total bacterial load in the mouth, maintaining or re-establishing the oral symbiotic equilibrium, and preventing the dissemination of oral bacteria to other sites in the body.

The characteristics of the oral microbiome are not only confined to oral pathological changes but can influence systemic health, and in cases, this influence is measurable in both positive and negative directions.

Diabetes

The strongest evidence supporting a bidirectional role between oral and systemic health exists for the dose-dependent relationship between the severity of periodontitis and complications arising from diabetes.

Type II diabetes is a metabolic disorder characterised by an insufficiency of insulin production and the subsequent inability for the body to metabolise glucose, leading to elevated levels of blood glucose (chronic hyperglycaemia). Severe periodontitis strongly influences glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and fasting blood glucose levels in people with and without diabetes [4]. Periodontitis is thus recognised as the sixth major complication of diabetes, as the risk for periodontitis is raised by 2-3 times for people with the condition [5].

19–33% Compared to individuals with periodontal health, patients with severe periodontitis are at a elevated risk of developing diabetes [6].

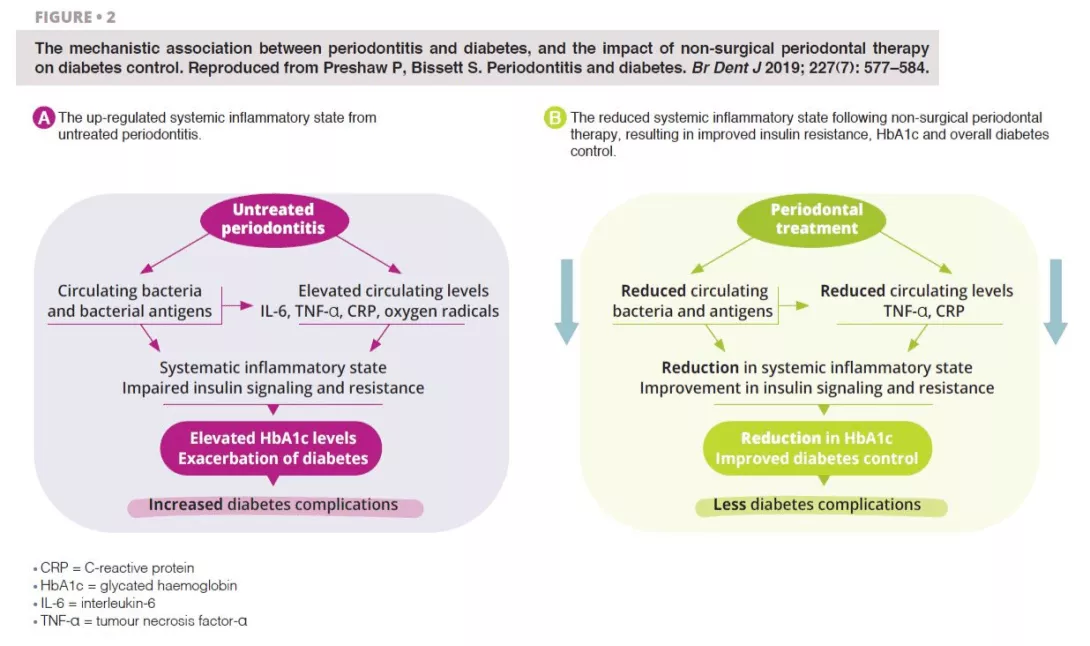

Untreated severe periodontitis is associated with an increase in the circulating levels of bacteria and bacterial antigens, pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines, and increased levels of interleukin 6, tumour necrosis factor alpha, C-reactive protein, and oxygen free radicals. This combined effect fosters the conditions for systematic inflammation, impairing insulin signalling and resistance [6]. Clinically, this is recognised through increased HbA1C and the progression of diabetes, with greater risk of diabetic complications. Periodontal treatment reduces the oral bacterial load, and therefore lowers the circulating levels of inflammatory mediators, thereby reducing the degree of the systematic inflammatory state (figure 2). Hence, the dental management of periodontitis can lead to a clinically-relevant improvement in glycemic control, where patients with diabetes experience HbA1c reductions of 0.3–0.4% up to four months after treatment.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Atherosclerosis describes the accumulation of fats, cholesterol, and blood cells that form hardened plaque deposits within the artery walls, occluding blood flow through the vessels, increasing the risk of cardiovascular complications.

Oral bacteria are contributory infectious agents in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, through the invasion of cardiovascular host cells, namely endothelial cells [7].

Chronic periodontal disease can lead to endothelial dysfunction, through an elevated systematic inflammatory state, which can be shown through increased levels of IL-6, fibrinogens, and periodontopathic bacterial products, such as outer membrane vesicles and gingipains [8]. Much of the atherosclerotic pathology appears to be attributable to Porphyromonas gingivalis. However, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia, Tannerella forsythia and Fusobacterium nucleatum have each been studied in relation to this association. The primary microbial implications are endothelial dysfunction and the promotion of atherosclerosis in cardiovascular cells. P. gingivalis has the ability to attach to endothelial target cells, and external factors mediate its cellular entry, where it induces pro-coagulant effects. The results of a parallel-group, single-blind, randomised, controlled trial found that although intensive periodontal therapy led to systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in the immediate term, 6 months after treatment, clinical and biochemical improvements in endothelial function were noted [9]. This study added to the theory that periodontal control may modulate atherosclerotic cardiovascular processes.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, autoimmune inflammatory condition affecting the synovial fluid of joints in a symmetrical pattern, and if untreated, other organs. Porphyromonas gingivalis is implicated in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis, where the bacteria produce enzymes with the capacity of citrullinating proteins, increasing the probability of reductions in the host immune tolerance and promoting the release of autoantibodies characteristic to the condition [10].

82% Cross-sectional data from the United States showed an 82% increase in rheumatoid arthritis associated with periodontitis, identified through gain in periodontal attachment loss [12].

Several studies have shown that periodontitis caused by dysbiotic oral biofilms, can trigger rheumatoid arthritis with systemic inflammation and increased bone erosion. A bidirectional relationship has been postulated between the inflammatory conditions, but further evidence is needed to verify this [11]. Clinicians involved in the rheumatological care of arthritis patients should be aware of the role of periodontitis as a factor modulating the efficacy of biologic disease- modifying anti-rheumatic therapies, since the maintenance of systemic inflammation could affect treatment response.

Non-surgical periodontal therapy appears to improve the biochemical expression of rheumatoid arthritis, but its role in improving clinical outcomes remains to be fully understood.

In patients with dysbiotic oral biofilms, where the proportions of periodontopathic bacteria capable of citrullinating proteins are higher than in health, preventive and curative treatment to stabilise the oral microbiome and periodontal inflammation would be prudent to include as a core aspect of the rheumatological care plan.

Prevention

Scientific advances in the understanding of the oral microbiome demonstrate its contribution to both oral and general health and well-being. The ecological plaque hypothesis is the currently accepted theory desiring microbiological changes in the mouth, where shifts in the ecology of the oral microbiome result in disharmony, which foster key harmful pathogens to increase in number [13]. The dissemination of oral bacteria to systemic bodily sites is substantially reduced by enhancing control of the oral microbial load. Daily mechanical removal of plaque, through a systematic and comprehensive toothbrushing and interdental cleaning technique, reduces the volume of this load, and prevents the colonisation of pathogenic species. Good plaque control also prevents the risk of developing periodontal diseases, characterised by micro-ulceration of the gingival architecture, thereby producing channels for the leakage of bacteria and inflammatory mediators.

Supplemented with professional interventions by dental practitioners (commonly oral hygiene instruction, risk factor control, and mechanical plaque removal), periodontal disease processes can be stabilised and if mild, reversed.

Where the microbial balance has been disturbed in disease, the symbiotic equilibrium of the oral microbiome can be re-established and stabilised through relatively simple personal and professional interventions.

Conclusion

Research exploring the association between changes in the oral microbiome and systemic chronic conditions continues to expand.There are multiple plausible reasons to justify the bidirectionality of these putative connections. Dysbiosis in the oral microbiome, the primary driver for local and general disease onset and progression is mediated by highly modifiable risk factors, reinforcing the value of prevention, and the need for health systems to re-orient their mode of care delivery to accommodate the delivery of preventive oral health care.

1. Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, et al.. The oral microbiome - an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J 2016; 221: 657–66.

2. Patel J, Sampson V. The role of oral bacteria in COVID-19. Lancet Microbe 2020; 1: e105.

3. GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1204–22.

4. Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 21–31.

5. Teeuw WJ, Kosho MX, Poland DC, Gerdes VE, Loos BG. Periodontitis as a possible early sign of diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2017; 5: e000326.

6. Preshaw P, Bissett S. Periodontitis and diabetes. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 577–84.

7. Tonetti MS, Van Dyke TE; working group 1 of the joint EFP/AAP workshop. Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Periodontol 2013; 84(Suppl 4): S24–S29.

8. Reyes L, Herrera D, Kozarov E, Roldán S, Progulske-Fox A. Periodontal bacterial invasion and infection: contribution to atherosclerotic pathology. J Clin Periodontol 2013; 40 (Suppl 14): S30-S50.

9. Tonetti MS, D’Aiuto F, Nibali L, et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 911–20.

10. Quirke AM, Lugli EB, Wegner N, et al. Heightened immune response to autocitrullinated Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase: a potential mechanism for breaching immunologic tolerance in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 263–9.

11. González-Febles J, Sanz M. Periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: What have we learned about their connection and their treatment? Periodontol 2000 2021; 87: 181–203.

12. de Pablo P, Dietrich T, McAlindon TE. Association of periodontal disease and tooth loss with rheumatoid arthritis in the US population. J Rheumatol 2008; 35: 70–6.

13. Marsh PD. Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv Dent Res 1994; 8: 263–71.