Rural environment reduces allergic inflammation by modulating the gut microbiota

COMMENTED ARTICLE - Children’s section

By Pr.Emmanuel Mas

Gastroenterology and Nutrition Department, Children’s Hospital, Toulouse, France

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Comment on the article by Yang et al. (Gut Microbes [1])

Rural environments and microbiota are linked to a reduction in the prevalence of allergies. However, the mechanism underlying this reduction is unclear. The authors assessed gut bacterial and fungal composition in urban and rural children in Southern China (EuroPrevall-INCO cohort). The bacterial and fungal composition of airborne dusts from homes in the city and countryside (including mattress dust) as well as dust from henhouses (rural environment) were analysed by 16S rRNA sequencing. Mice were repeatedly exposed to intranasal dust extracts and evaluated for their effects on ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway inflammation. It was found that children in rural areas had fewer allergies and unique gut microbiota with fewer Bacteroides and more Prevotella. Dusts from rural environments contained a higher level of endotoxins and diversity of bacteria and fungi, whereas indoor urban dusts were enriched with Aspergillus and contained a higher number of potentially pathogenic bacteria. Intranasal administration of rural dusts before OVA sensitisation reduced respiratory eosinophils and blood IgE level in mice and also led to a recovery of gut bacterial diversity and Ruminiclostridium in the mouse model. Faecal microbiota transplant restored the protective effect by reducing OVA-induced lung eosinophils in recipient mice. These results support a cause-effect relationship between exposure to dust microbiota and allergy susceptibility in children and mice. Specifically, rural environmental exposure modulated the gut microbiota, which was essential in reducing allergy in children.

What do we already know about this subject?

The prevalence of allergic diseases has increased dramatically. It has been shown that children living in the countryside are less prone to asthma than those living in cities. Indoors, dust is the main source of bacteria and fungi. Its composition reflects the outdoor environment and is influenced by external activities (e.g., agricultural), building materials and animals.

The establishment of gut microbiota during the first 1,000 days of life shapes the subsequent development of allergic diseases. Some well-known factors influence the composition of the gut microbiota of infants including antibiotics, delivery method and diet. Any resulting dysbiosis is thought to increase the subsequent likelihood of developing allergic diseases. In contrast, breastfeeding and vaginal delivery protect against the subsequent development of allergic diseases. The intestinal microbiota of these types of infants is characterised by a predominance of bifidobacteria, especially Bifidobacterium breve. Decreased contact with nature was seen to favour intestinal dysbiosis with a dysregulation of Th1/Th2 immune balance in favour of Th2, which is the adaptive immune response involved in allergic diseases (Cukrowska Nutrients).

The mechanisms by which gut dysbiosis in early life influences the development of allergies and asthma are little understood. Farm dust and bacterial lipopolysaccharide are known to induce endotoxin tolerance, thus reducing allergic asthma.

What are the main insights from this study?

The authors compared urban and rural environmental exposures in China in a human and mouse study. The EuroPrevall-INCO human cohort included 5,139 urban and 5,542 rural school-age children. The prevalence of food allergies and especially asthma, rhinitis, and eczema were higher in urban children (p < 0.001).

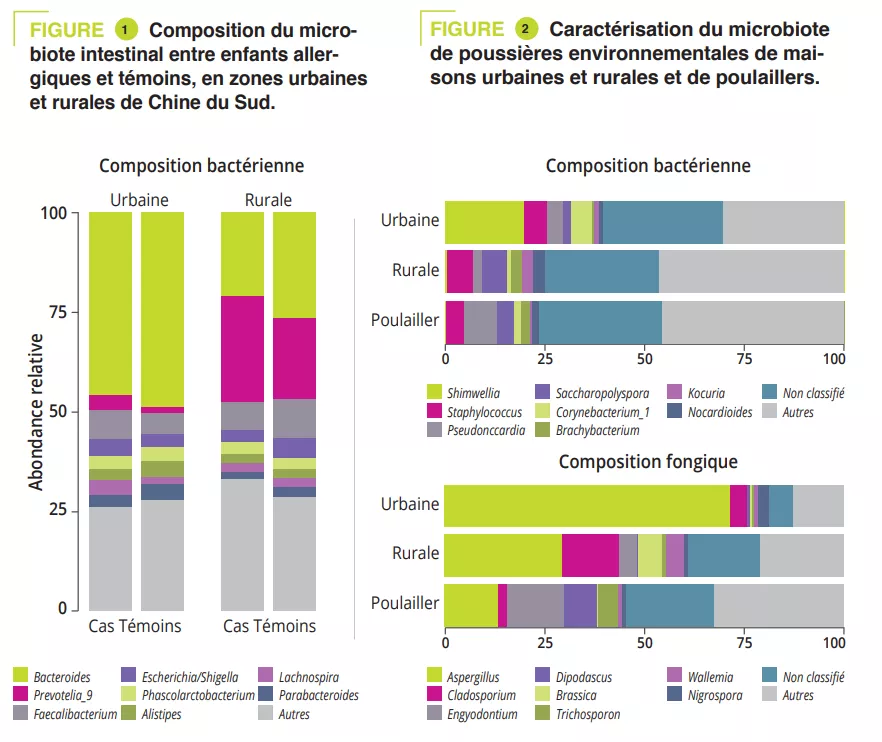

A case-control study included 225 children: 151 urban and 74 rural children. The gut microbiota of all children was analysed via 16S rRNA sequencing and metabolic pathways were assessed via shotgun sequencing. Clinical data and allergen sensitizations were collected. The Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio was significantly higher in rural children (p < 0.001). This difference was due to Prevotella_9 accounting for 25% of amplified variants in rural children and <5% in urban children (figure 1). However, no significant difference was observed in gut microbiota composition between cases and controls in both urban and rural participants. The analysis of metabolic pathways identified 14 different pathways between urban/rural participants and nine between controls/ cases. Among these, the L-lactate producing pathway was strongly associated with allergy and pathways involved in sugar degradation and lipopolysaccharide synthesis were abundant in the microbiota of control children.

To mimic the microbial exposure of children in urban and rural environments, mattress dusts were collected from ten urban and ten rural families and dusts from five henhouses from rural families (on the assumption that these may contribute to the microbial environment in rural families). Enterobacteriaceae and Rhizobiaceae were predominant only in urban house dusts (figure 2). A significantly higher a diversity and endotoxin content was observed in rural house dusts compared to urban house dusts and henhouse dusts. Finally, urban house dusts had a significantly higher proportion of potentially pathogenic bacteria. In addition, Aspergillaceae dominated in urban house dusts, whereas Trichocomaceae (genus Penicillium) was more abundant in rural house dusts (hence the higher diversity) and henhouse dusts (figure 2).

KEY POINTS

- Chinese children living in rural areas develop fewer allergic diseases than those living in urban areas

- The composition of the dust microbiota is different

- In mouse models, exposure to rural house dusts reduces allergic inflammation in the airways by modulating the gut microbiota

To test the impact that exposure to environmental dusts may have on allergic disease by altering the gut microbiota, the researchers exposed mice to dust by intranasal exposure (OVA-induced allergic model). Prior exposure to house dust in rural areas attenuated allergic inflammation (eosinophilic infiltration of airways, in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), increased sIgE). Mice exposed to rural dusts showed the lowest increase in the proportion of potentially pathogenic bacteria. The abundance in the gut of Bacteroidales increased and while Clostroidales (including species belonging to both Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae families) decreased in control mice exposed to PBS as well as those exposed to urban dusts. Finally, the relative abundance in the gut microbiota of Bacteroides and Ruminiclostridium was correlated to eosinophils in BAL (r = 0.59 and p = 0.001 and r = – 0.45 and p = 0.05 respectively).

What are the consequences in practice?

Early modulation of the gut microbiota, targeting the beneficial effect of rural house dusts could prevent the development of allergic diseases.

CONCLUSION

This study reported differences in the composition of dust microbiota between urban and rural areas in China. These modulate differently the gut microbiota and its immune response in allergic diseases.