Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), previously called a “functional bowel disorder”, is the most common gut-brain axis disorder. Symptoms include recurrent abdominal pain, bloating and bowel dysfunction. Its main symptoms involve the bowels, but IBS can often also be associated with anxiety and depression. We have now established links with communication disruptions in the gut-brain axis, in which gut microbiota play a role.

- Learn all about microbiota

- Microbiota and related conditions

- Act on your microbiota

- Publications

- About the Institute

Healthcare professionals section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Table of contents

Table of contents

5 to 10% of the world's population has IBS.

(sidenote: Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2020 Nov 21;396(10263):1675-1688 )

Did you know?

Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI) are also known as “functional bowel disorders”. We say they are “functional” because there are no structural abnormalities of the digestive organs or tissues. Other terms used for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) include “functional colopathy”, “spastic colitis” and “irritable colon syndrome” 2.

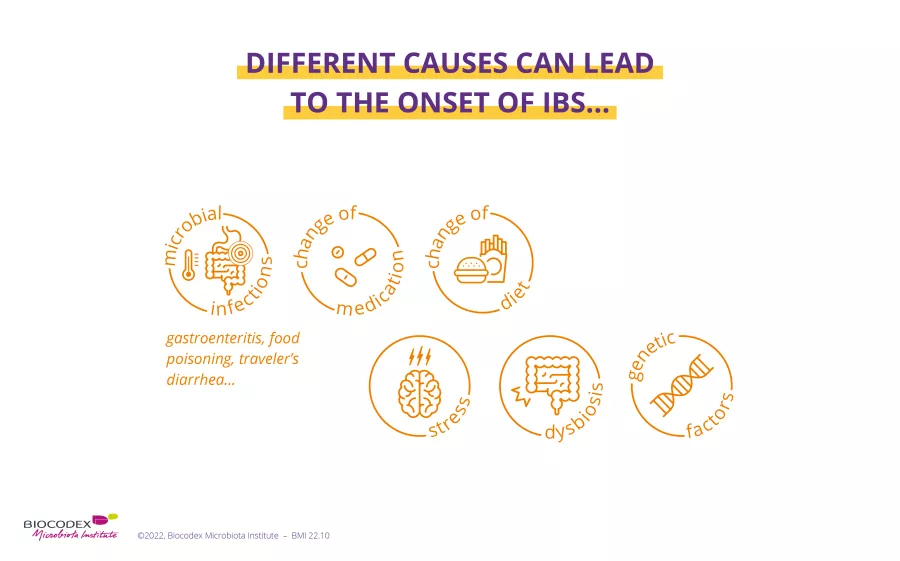

What causes irritable bowel syndrome?

The causes of irritable bowel syndrome are complex, and not yet fully identified. IBS is thought to be triggered by a combination of different factors, the importance of which varies from person to person 2: genetic predisposition, certain medical histories and treatments, stress, diet, etc.

The most well-known risk factor for IBS is a history of acute intestinal infection: 10% of people with IBS believe their problems began after such an episode, for example viral gastroenteritis, traveler’s diarrhea or (sidenote: Diverticulitis Diverticulitis is an inflammation or infection of the diverticula, small folds (hernias) in the inner wall of the colon. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/diverticulitis ) 1,4,5. The risk of developing IBS seems to be quadrupled after one year following this type of infection 1.

2 out of 3 IBS sufferers in Western countries are women.

50 The frequency of IBS decreases after the age of 50.

(sidenote: SNFGE. Syndrome de l’intestin irritable (SII) [Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)]. June 2018. CNPHGE. Syndrome de l’intestin irritable [Irritable bowel syndrome]. )

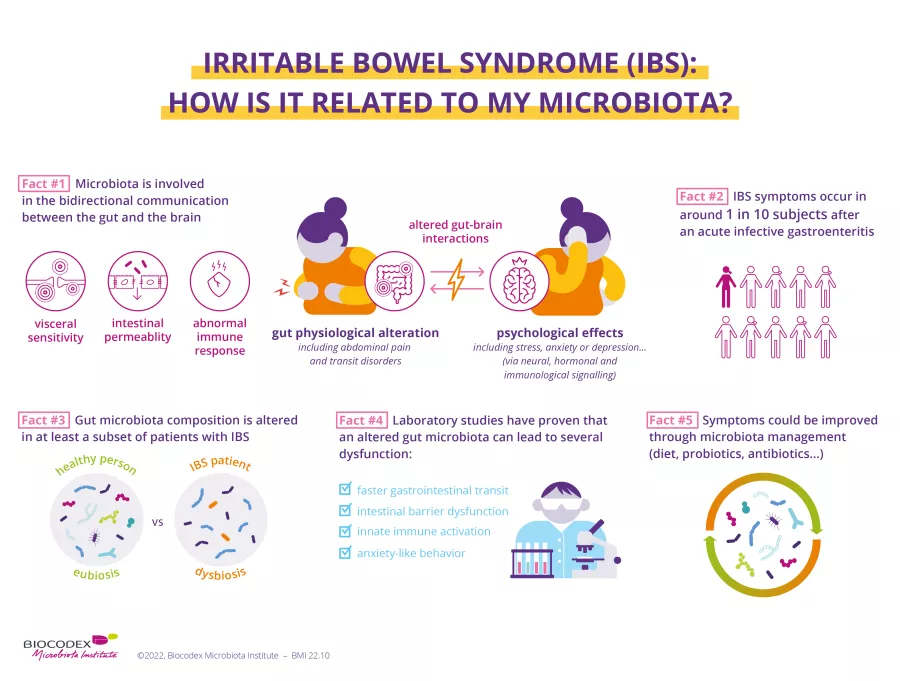

Recent research is increasingly suggesting that the gut microbiota play a key role in the development of IBS 6,7. Experts have even recognized an imbalance in the composition of the gut microbiota, or dysbiosis, as a plausible cause of IBS 5. Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis has also been associated with the development of IBS 1.

The scientific community is also showing strong interest in the role of diet in IBS. Over 60% of IBS patients say their symptoms appeared or worsened after eating 8,9. This is labeled as bowel hypersensitivity. The presence of certain food compounds (wheat, milk, etc.) appears to trigger an exaggerated reaction in the gut, which can be immune-related 10,11. Moreover, dietary habits often disturb the gut microbiota and cause abnormal fermentation of ingested food, thought to play a crucial role in intestinal distension 10.

The gut microbiota

IBS is also triggered by traumatic or distressing events (bereavement, divorce, abuse, conflict, etc.), and by acute or chronic stress and other psychological disorders such as depression or anxiety 1,2,7. These appear to exert a negative impact on the (sidenote: The enteric nervous system The enteric nervous system (ENS) is the nervous system of the gut. It is composed of a network of neurons that line the walls of the gastrointestinal tract and controls the sensory, motor and secretory activity of the digestive system. Watson C., Kirkcaldie M., Paxinos G. The brain: an introduction to functional neuroanatomy – Chapter 4 - Peripheral nerves. Academic Press, 2010. 43-54 ) , which controls motor function, the mucosal barrier, sensory function and intestinal secretions 1.

Could poor communication between the gut and brain explain IBS?

Does the gut-brain axis mean anything to you? The brain communicates with the enteric nervous system in both directions: what happens in the brain affects the gut, and vice versa. But that is not all: neurons in the gut are linked directly to the gut microbiota, which also maintains bidirectional communication with our hormonal and immune systems.

How our gut constantly talks to our brain

IBS disturbances cause:

the brain perceives normal gut movements as pain;

the intestines contract abnormally;

(in 50% of cases), excessive immune stimulation after an infection 5 or hypersensitivity to certain foods 6;

fragments of bacteria are able to pass out of the gut, causing chronic diffuse inflammation 7,12;

occurs in 2 out of 3 of people with IBS, and is potentially involved in all the above IBS disturbances and symptoms 2,7.

What are the main symptoms of IBS?

According to well-established criteria, IBS is characterized by the simultaneous presence of several symptoms, involving abdominal pain and bowel dysfunction. These symptoms must be sufficiently frequent and long-standing (>1 day/week in the past 3 months) 13,14:

- Recurrent abdominal pain (at least 1 day a week);

- Painful defecation;

- Bloating;

- Change in stool consistency;

- Change in stool frequency.

Some clarification and explanation may be useful!

Abdominal pain is manifested by spasms, burning sensations, tightness and bloating. It occurs around the navel, in the lower abdomen, and can appear to follow the course of the colon. The pain is associated with defecation, and can be aggravated or relieved by the emission of gas or stools 2.

Abnormalities in stool consistency and frequency range from stools that are too soft and/or too frequent (as in diarrhea) to stools that are too hard and/or too infrequent (as in constipation). There may be alternating periods of diarrhea and constipation. These transit disorders are sometimes accompanied by other types of discomfort, including an urgent need to pass stools, presence of mucus in stools or an impression of incomplete stool evacuation 5.

These changes in stool frequency and consistency allow IBS to be classified as one of four subtypes:

- IBS-C: Constipation predominant IBS (at least 1 in 4 stools);

- IBS-D: Diarrhea predominant IBS (at least 1 in 4 stools);

- IBS-M: Mixed diarrhea and constipation IBS (at least 1 in 4 stools are constipation predominant, and 1 in 4 are diarrhea predominant). This is the most common subtype (40% of people with IBS);

- IBS-U: Unclassified IBS, not meeting the criteria for IBS-C, D or M. Abnormal stools are rare 15,16.

It is worth noting that someone with IBS can develop a different subtype over time 3.

IBS symptoms vary in severity from person to person, and over time in the same person 3,5. They can range from being inconvenient to very disabling, with severe forms of IBS affecting 20-25% of patients 3. Generally speaking, they affect personal, social and professional quality of life 1,3.

Only physicians can diagnose IBS, once they have successfully ruled out another digestive disorder 2. There is no diagnostic test for IBS as yet, so physicians rely on patients’ descriptions of symptoms; the results of clinical examinations and imaging carried out in people with IBS are generally normal 3.

Which disorders and conditions are associated with IBS?

Generally speaking, people with IBS are more likely to suffer from certain disorders and conditions.

- Other digestive disorders: In over 20% of cases, IBS is accompanied by bloating, flatulence 4, nausea or heartburn 16. Some people are also intolerant of certain foods 5.

- Psychological disorders: Not only can psychological factors play a role in causing IBS, but a proportion of sufferers may also develop psychological disorders as a result of IBS 1, for example anxiety, stress, depression, insomnia or eating disorders 5.

- Genitourinary disorders: IBS may be accompanied by pelvic pain, urinary disorders, pain during intercourse in women and erectile dysfunction in men 4,5.

- Endometriosis: Studies have shown that women with endometriosis are three times more likely to develop IBS 17.

- General disorders: Some people with IBS experience fatigue, lethargy, headaches and/or muscle pain 2,4,5. IBS is more common in people with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue 1.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome and microbiota: is there a link?

How to treat your IBS?

Although painful and challenging to live with in everyday life, IBS is a benign disorder 2. Despite this, IBS symptoms should be relieved as soon as possible to improve quality of life 3. Your physician will give you lifestyle tips and recommend an optimal combination of specific medications and alternative solutions.

Good nutritional habits can alleviate IBS symptoms 6,18:

- eat meals at regular times and avoid skipping meals;

- avoid “pantagruelian” meals and spicy or greasy dishes;

- chew food well;

- drink enough fluids;

- limit alcohol, caffeine and tobacco;

- engage in regular physical activity.

Medication

Some IBS symptoms can be improved by taking physician-prescribed medication, for example antispasmodics, intestinal transit regulators, laxatives in case of IBS-C, antidiarrheals in case of IBS-D, and sometimes antidepressants 9. But these drugs are not effective in everyone 16, and to date none have been shown to relieve all IBS symptoms.

Mind-body therapies

(sidenote: Mind-body therapies Mind-body therapies are practices that focus on the relationships between the body, brain, mind and behavior and their effects on health and disease. Wahbeh H, Elsas SM, Oken BS. Mind-body interventions: applications in neurology. Neurology. 2008;70(24):2321-2328 ) can reduce pain and discomfort associated with bowel disorders, particularly in people in whom stress and anxiety can exacerbate symptoms. Examples include (sidenote: Cognitive-behavioral therapy A type of psychotherapy where therapists help patients to identify the impact of their dysfunctional thoughts (incorrect, negative) on their behavior and well-being. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E, et al. Efficacy of cognitive–behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta-analytic study of publication bias. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):173-178 InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006. Cognitive behavioral therapy. 2013 Aug 7 [Updated 2016 Sep 8] ) , hypnosis, meditation, relaxation and (sidenote: Biofeedback A method for learning how to control certain bodily functions, such as heart rate, blood pressure and muscle tension, using a special device. It can help control pain. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/biofeedback ) 16.

Diets

Many people with IBS find that certain foods improve or aggravate their symptoms, but they are not the same for everyone. Modifying the diet can therefore improve IBS symptoms, but this should always be done with the help of a health professional (physician, dietician), to work out a personalized solution and prevent any nutritional imbalance 16.

For example, your physician can help you detect any foods that “don’t work for you” (milk, wheat, legumes, etc.), to then limit their intake 9. You can also include more fiber in your diet if you have IBS-C, although not in excess to avoid increased risk of pain and bloating 6.

Dietary practices shape the composition of microbiota

Of the diets tested scientifically, the low FODMAPS diet (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols), seems to give the best results in relieving IBS 6,16 although it does not work for everyone 2. FODMAPs are sugars that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and ferment through the action of gut microbiota bacteria. This fermentation exacerbates bloating and pain in people with IBS.

The diet consists in significantly reducing intake of foods rich in FODMAPs, which are foods containing lactose, certain cereals, certain fruits and vegetables, synthetic sweeteners, processed foods, etc. It can be restrictive, it requires supervision by a physician, and must be monitored for 4 to 6 weeks. If symptoms improve, foods containing FODMAPs are then gradually reintroduced one by one. In this way it will be possible to determine which food(s) aggravate your symptoms and avoid them 2,19.

Probiotics, prebiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation

Various studies have highlighted the importance of the gut microbiota in the occurrence of IBS, and shown differences in the composition of gut microbiota between affected and healthy individuals 5. Solutions may therefore be proposed to modulate the gut microbiota, with the aim of improving IBS symptoms 20.

According to experts, prebiotics are a promising option. Studies show that they have an overall positive effect on IBS symptoms by acting on various mechanisms, such as visceral hypersensitivity and intestinal motility 9. Probiotics can strengthen the colonic barrier, reduce inflammation and improve gut immunity, for example 20. Some may even act on the gut-brain axis and improve depressive symptoms 9. All these effects appear to be beneficial to well-being: in a recent study, consumption of a strain of bifidobacteria reduced symptom severity and improved quality of life in 60% of people with IBS in 30 days 21.

Studies on the effect of symbiotics on IBS, which combine probiotics and prebiotics, are also underway 9, and initial testing of fecal microbiota transplantation has yielded encouraging results in some patients with IBS who have seen an improvement in both symptoms and quality of life 1.

62% of respondents thought that consuming probiotics helped to maintain healthy microbiota balance and function

What exactly are probiotics?

Prebiotics: what you need to know

BMI 23.11

1. Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2020 Nov 21;396(10263):1675-1688

2. SNFGE. Syndrome de l’intestin irritable (SII) [Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)]. June 2018. https://www.snfge.org/content/syndrome-de-lintestin-irritable-sii

3. CNPHGE. Syndrome de l’intestin irritable [Irritable bowel syndrome]. https://www.cnp-hge.fr/syndrome-de-lintestin-irritable/

4. Moayyedi P, Mearin F, Azpiroz F, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis and management: A simplified algorithm for clinical practice. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(6):773-788

5. Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16014

6. Algera J, Colomier E, Simrén M. The Dietary Management of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Narrative Review of the Existing and Emerging Evidence. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):216

7. Hillestad EMR, van der Meeren A, Nagaraja BH, et al. Gut bless you: The microbiota-gut-brain axis in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2022 Jan 28;28(4):412-431

8. Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, et al. Self reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol 2013, 108:634–641

9. Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, et al. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63:108–115

10. Cuomo R, Andreozzi P, Zito FP, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and food interaction. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul 21;20(27):8837-45

11. Hussein H, Boeckxstaens GE. Immune-mediated food reactions in irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022;66:102285

12. INSERM: La rage au ventre: C’est quoi le syndrome de l’intestin irritable ? [Rage in the belly: What is irritable bowel syndrome?] (Sep 14, 2021) https://www.inserm.fr/c-est-quoi/la-rage-au-ventre-cest-quoi-le-syndrome-de-lintestin-irritable

13. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;S0016-5085(16)00222-5

14. Drossman DA, Tack J. Rome Foundation Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(3):675-679

15. Black CJ, Ford AC. Global burden of irritable bowel syndrome: trends, predictions and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 17: 473-86

16. Chey WD, Keefer L, Whelan K, et al. Behavioral and Diet Therapies in Integrated Care for Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):47-62

17. Chiaffarino F, Cipriani S, Ricci E, et al. Endometriosis and irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;303(1):17-25

18. Okawa Y. A Discussion of Whether Various Lifestyle Changes can Alleviate the Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Healthcare. 2022; 10(10):201

19. Société Nationale Française de Colo-Proctologie [French National Society of Coloproctology]: Régime pauvre en FODMAPs [Low FODMAP diet] (December 2021) https://www.snfcp.org/informations-maladies/generalites/regimes-pauvre-en-fodmaps

20. Simon E, Călinoiu LF, Mitrea L et al. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics: Implications and Beneficial Effects against Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nutrients. 2021;13(6):2112

21. Sabaté JM, Iglicki F. Effect of Bifidobacterium longum 35624 on disease severity and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2022 Feb 21;28(7):732-744