Viral diarrhea: will vaccines change the game ?

Usually presenting as watery diarrhea, viral diarrheas are caused by 5 main types of virus. Among them, rotavirus remains the leading cause of diarrhea-related mortalities in children under 5 years of age, this despite the availability of vaccines since 2006. Composition of the gut microbiota, implicated in viral infection outcomes, and rotavirus vaccine efficacy, could play a key role in strategies aimed at reducing the burden of viral diarrhea.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Rotaviruses, norovirus, sapovirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus: five virus types are currently recognized as the main causes of viral diarrhea.21

Of the 2 billion plus episodes of diarrheal disease that occur across the world each year, as estimated by the 2016 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study,2 almost 900 millions of the moderate-to-severe episodes were attributed to just three of these viruses: rotavirus, norovirus and adenovirus22.

ROTAVIRUS, THE NUMBER ONE DIARRHEAL KILLER IN CHILDREN

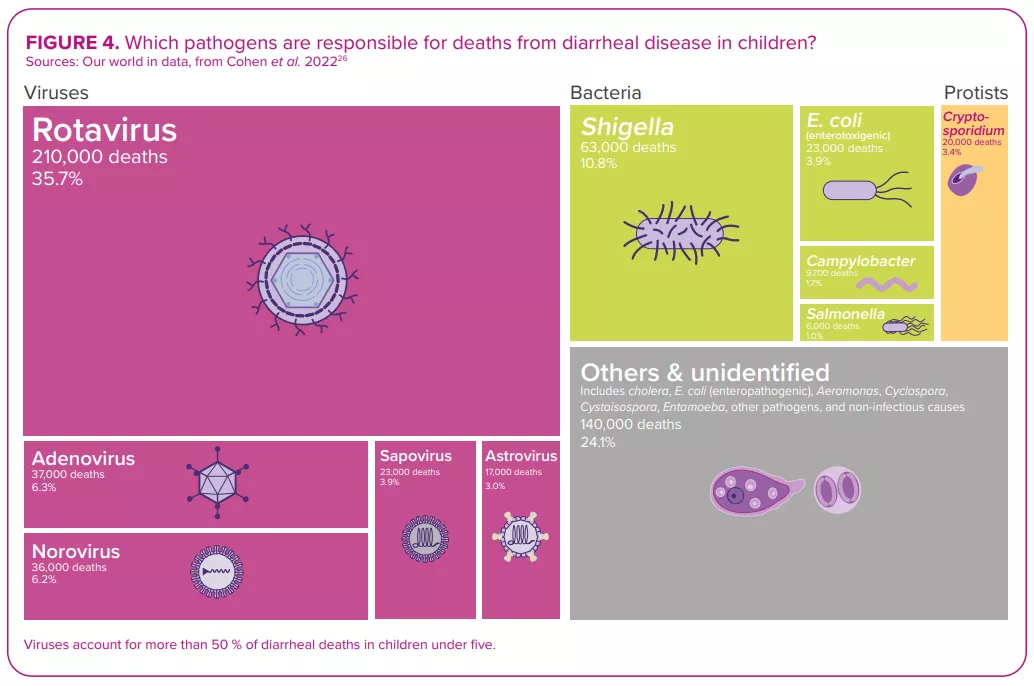

Despite the development and availability of rotavirus vaccines since 2006,22 this virus, which causes more severe symptoms than most other enteric pathogens,22 was still responsible for over 228,000 deaths worldwide in 2016, of which over 128,000 occurred in children below the age of 52 – making rotavirus the leading cause of diarrhearelated mortalities among this segment of the population (Figure 4).

WATERY DIARRHEA

Whatever the virus that triggers an episode of diarrhea, the process of infection is broadly the same: the virus infects the epithelial cells of the small intestine and causes damage that hampers the absorption of fluid.21 Viral diarrhea usually manifests itself in the form of a watery (non-bloody) diarrhea. It can be accompanied by other symptoms, i.e. nausea, abdominal cramps, vomiting and fever,22 resulting in what is known as viral gastroenteritis.

REHYDRATION… AND PROBIOTICS

Just as for the other etiologies (bacterial or parasitic) of infectious diarrhea, management of viral diarrhea relies on oral or intravenous fluid replacement therapy, depending on the degree of dehydration.21 In addition, according to the latest conclusions of the ESPGHAN committee (2023),20 healthcare professionals may recommend some probiotic strains (L. rhamnosus, S. boulardii and L. reuteri) for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children, since there is some evidence (certainty of evidence: low; grade of recommendation: weak) of reduced duration of diarrhea, and/or length of hospitalization, and/or and stool output.

Among all diarrheal pathogens, and despite vaccine availability, rotavirus remains the number one killer of children under five years of age. 2

IMPROVING ROTAVIRUS VACCINE EFFICACY, A CHALLENGE YET TO OVERCOME

Regarding prevention, the usual preventive measures apply (ensuring safe drinking water, adequate sanitation and frequent handwashing, limiting contact with infected people, etc.). Given the considerable burden of rotavirus diarrheal disease, rotavirus vaccines are another important preventive measure. 22,23

SARS-COV-2: NEW MEMBER OF THE DIARRHEAL VIRUSES CLUB

Alongside the viruses long recognized as principal causes of viral diarrhea, infection with the SARS-CoV-2, responsible for the greatest pandemic in recent times, COVID-19, may also give rise to diarrhea. In clinical studies, the incidence rate of diarrhea ranges from 2% to 50% of cases. 27 As with the respiratory tract, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors are highly expressed on intestinal cells, serving as an important site of entry for the virus in the gut. The putative mechanisms leading to the development of diarrhea mainly involve angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 dysregulations following virus entry into enterocyte, which could trigger an inflammatory response, ionic imbalance and increased permeability. Furthermore, the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 acts as an enterotoxin, with a mechanism similar to the rotavirus enterotoxin NSP4.28 Alteration of gut microbiota and side effects of medications (antiviral and antibiotics) are also thought to be involved.29

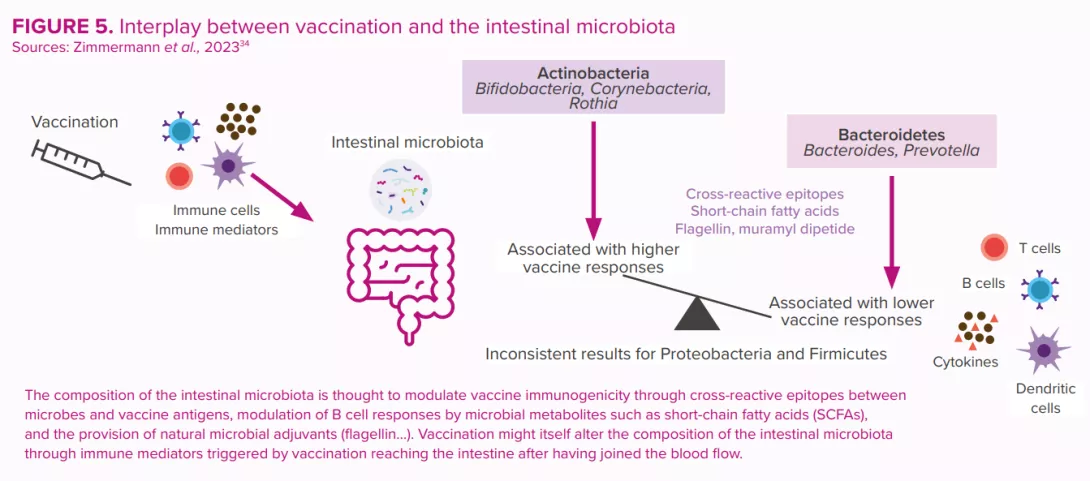

Microbiota: a key role in rotavirus vaccination efficacy

Since their introduction in 2006, oral rotavirus vaccines (ORVVs) have at a global level led to a significant drop in the number of hospitalisations and deaths due to rotavirus diarrhea.30 However, the efficacy of the vaccines has been varied, with low-income countries suffering from lower performance compared to the remarkably high efficacy (>90%) observed in higher income countries.31 Reasons for this disparity are thought to be multi-factorial (host immunity, perinatal outcomes, genetics, nutritional status, stress, tobacco and alcohol use, rural versus urban location, family size, etc.). Just as for other vaccines, the composition and function of the gut microbiota is considered to be a key factor that regulates the immune response to vaccination30,32,33 (Figure 5).

These were estimated to have prevented 139,000 deaths from rotavirus among under-fives during the period 2006 to 2019, and to have prevented 15% of under-five rotavirus deaths in 2019.24 However, vaccine efficacy is region-specific and displays poor seroconversion in low-and middle-income countries. Human clinical trial data have suggested a possible link between the gut microbiota and the enteric immune system’s response to rotavirus vaccine25 (Figure 5).

Each gram of human gut content is estimated to contain at least, 108 –109 virus-like particles, the vast majority of which are phages.14

MICROBIOTA: FRIEND OR FOE IN THE ONSET OF VIRAL DIARRHEA?

In cases of viral diarrhea, as with infectious diarrhea in general, the outcome of the confrontation between pathogen and host depends on complex balances that in large part involve the microbiota.

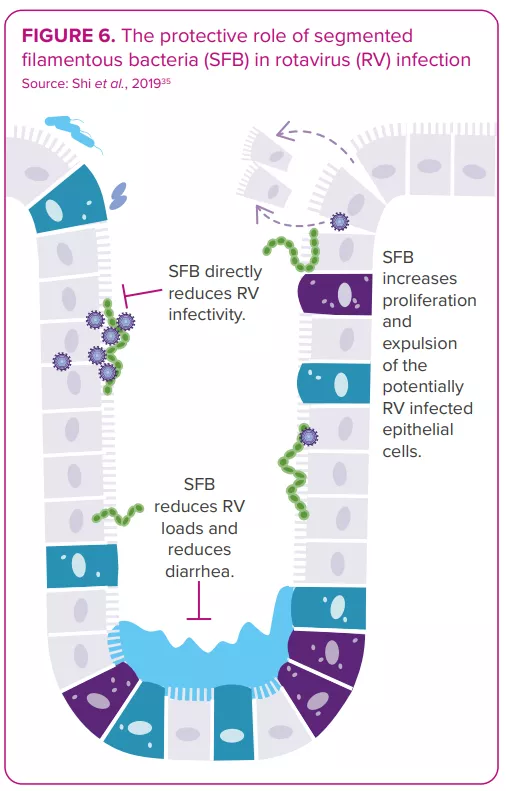

The gut microbiota displays bidirectional interactions with rotavirus and norovirus infections:14 it can either protect against or predispose the host to infection; in turn, an infection can alter the gut microbiota. Some bacteria seem able to inhibit viral infection. For example, one study shows segmented filamentous bacteria preventing and curing rotavirus infection in mouse colonies35 (Figure 6). On the other hand, in vitro and in vivo studies indicate the gut microbiota’s involvement in facilitating viral infection: certain gut microbes (e.g. Enterobacter cloacae) stimulate the ability of human norovirus to infect human B cells in vitro; microbiota elimination by antibiotics delays infection, reduces infectivity and/or viral titer of norovirus and rotavirus in mice.8,36

Therefore, any invasive pathogens might have different effects depending on the state of the gut microbiota. 3 The optimal microbiota profile and microbiota-targeting strategies that would lower the risk of infection and the following viral diarrhea remain to be characterized.37

As to the effect of viral infection on gut microbiota composition, numerous studies have documented specific patterns of dysbiosis in patients suffering from viral diarrhea compared to healthy controls25,38. A reduction of microbiota (alpha) diversity is often reported, but specific taxa increases or decreases vary widely across the studies.14 And one question remains: does the dysbiosis observed during viral diarrhea reflect a prior disposition that might have facilitated the infection, is it a state caused by the virus, or is it a combination of both?

CLINICAL CASE by Dr. Marco Poeta

- A 4-year-old girl presented to the paediatric emergency room with fever, diarrhea, vomiting and severe dehydration.

- Since the child needed intravenous rehydration, she was admitted to the hospital.

- The nasopharyngeal swab returned positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection, despite the absence of respiratory symptoms.

- Stools were negative for rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus, bacteria and parasites but positive for SARS-CoV-2.

- Following the administration of probiotics, her stool frequency and consistency both recovered.

- The intravenous hydration was discontinued after four days, and the child was discharged.

- Diarrhea can be the only clinical manifestation of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 should therefore be added to the list of enteric pathogens.

- The efficacy of probiotics against Covidassociated gastroenteritis observed in this clinical case has already been demonstrated via in vitro studies.

EXPERT OPINION

Probiotics are recommended as an active means of treating of viral diarrhea in children, exerting an antidiarrheal effect that restores microbiota composition from its altered state. In clinical trials, some probiotic strains reduce secretory diarrhea in a very short time, measurable within hours after the start of probiotic administration. Considering that several days are normally required to establish changes in the composition of the microbiota, the rapid efficacy of probiotics implies that there are additional positive effects. Molecules secreted by the bacteria that act directly on intestinal cells can inhibit secretory diarrhea through an antioxidant mechanism. This is defined as the "postbiotic effect". The metabolites produced by probiotics have pharmacological-like action and could represent innovative therapies for the management of viral diarrhea.