Parasitic diarrhea: can the microbiota shape clinical outcomes ?

Not all individuals respond to intestinal infections of parasites in the same way: while some develop no symptoms at all, others experience more or less severe diarrhea, which can lead to death. The gut microbiota is increasingly cited as a key factor in explaining this variability

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Intestinal parasites can be broadly classified into protozoa (single cell organisms) and helminths (multicellular, known as worms).39 Globally, there are an estimated 895 million people infected with soil transmitted helminths (STH). Intestinal protozoa (IP) have a lower overall prevalence rate, but still, over 350 million people are believed to be infected with 3 of the most common protozoan parasites40. Protozoan infections are common in low and middle income countries (LMICs). Food-chain globalisation, international travel and migration are leading to an increase in protozoan infections in high income countries, where they are more common than intestinal helminth infections.39

Giardiasis, the most common parasitic diarrhea worldwide, affects 280 million people each year. 41

DIARRHEAS CAUSED BY PROTOZOAN PARASITES

The most common intestinal protozoan parasites are Giardia intestinalis (Giardia duodenalis or Giardia lamblia), Entamoeba histolytica, Cyclospora cayetanensis, and Cryptosporidium spp. Diarrheal diseases caused by these pathogens are known respectively as giardiasis, amebiasis, cyclosporiasis and cryptosporidiosis.41

Giardia intestinalis infects the upper small intestine altering its barrier and permeability. Between 6 and 15 days after infection, it can cause acute, watery diarrhea associated with abdominal cramps, bloating, nausea and vomiting. Giardiasis, the most common parasitic diarrhea worldwide, affects 280 million people annually. 41

Entamoeba histolytica infections are usually asymptomatic but can produce an invasive disease of the large bowel (notably in immunocompromised patients) and amebic dysentery can develop. The acute phase lasts 3 weeks, with abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea and mucus in the stools. Accounting for over 26 000 deaths annually,2 amebiasis is the third leading cause of death from parasitic infections worldwide; it particularly affects people in LMICs.41

Cyclospora cayetanensis is the only species of the genus Cyclospora that can infect humans. After an incubation period which may vary from 2 to 12 days, it typically manifests as voluminous watery acute diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, low grade fever, fatigue and weight loss.41

Cryptosporidium spp. infection symptoms appear after one or two weeks of incubation: the most common clinical symptoms are acute watery diarrhea, abdominal cramps, malabsorption, nausea, vomiting and fever, lasting for approximately 5 to 10 days.41 An estimated 64 million cases of cryptosporidiosis are reported each year.40

Helminth parasites and the microbiota have coexisted within their hosts, for millions of years. 50

TRAVELERS’ DIARRHEA: PARASITIC INFECTION IS COMMONLY ASSOCIATED WITH PI-IBS

While the majority of travelers’ diarrhea cases are acute and resolve spontaneously, a subset of individuals will experience persistent gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms potentially extending for weeks, months, or even years, after the initial cause has been effectively treated.52 A recent publication suggests that nearly 10% of patients experiencing travelers’ diarrhea develop persistent symptoms consistent with post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PIIBS). Parasitic infection, particularly giardiasis, is commonly associated with PI-IBS.53

DIARRHEAS CAUSED BY SOIL-TRANSMITTED HELMINTHS

Globally, the principal soil-transmitted helminths are the roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), the whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) and hookworms (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale). Symptoms experienced following helminth infection are related to the number of worms harboured: people with infections of light intensity (few worms) do not usually experience discomfort, whereas heavier infections can cause a range of symptoms including some that manifest in the intestine (diarrhea and abdominal pain), malnutrition, general malaise and weakness, and impaired growth and physical development. Soiltransmitted helminths contribute to the burden of diseases by impairing the nutritional status of the people they infect in a variety of ways: they feed on host tissues, cause intestinal blood loss and hamper the absorption of nutrients.42

- Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common intestinal nematode that infects humans, with an estimated 807 - 1,221 million people infected each year. 43 Infection commonly occurs without symptoms. The symptomatic form is characterized by an early lung phase followed by a later intestinal phase, which is characterized by diarrhea, mild abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea and vomiting.41

- An estimated 604-795 million people in the world are infected with Trichuris trichiura. People with heavy infections can experience frequent painful bowel movements that contain a mixture of mucus, water and blood.44

- An estimated 576-740 million people in the world are infected with hookworms, usually without symptoms. Few people, especially those infected for the first time, experience gastrointestinal symptoms. The most common and serious effects of hookworm infection are intestinal blood loss leading to anaemia, in addition to protein loss.45

MICROBIOTA: A ROLE IN THE MARKED CLINICAL VARIABILITY OF PARASITIC DIARRHEA?

Parasitic protozoan infections are characterized by marked variability in their clinical presentation: they can be asymptomatic or cause diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, etc. Recent studies have highlighted the potential contribution of the intestinal microbiota to this clinical variation: for instance, an abundance of Prevotella copri in the gut microbiota predicted diarrhea in the context of Entamoeba histolytica infection;46 low Megasphaera abundance prior to and at the time of Cryptosporidium detection was associated with parasitic diarrhea in infants in Bangladesh, suggesting that the gut microbiota may play a role in determining the severity of a Cryptosporidium infection.47 In turn, infection by protozoan parasites alters the gut microbiome.48,49

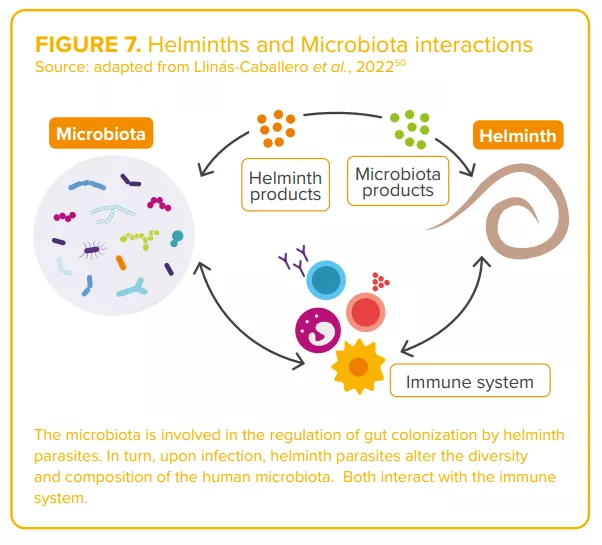

Regarding helminths, the complex interactions between worms and the microbiota (“two of humans’ old friends” 50) are currently under study50 (Figure7). Authors agree on the existence of a complex and dynamic interplay between parasite(s), the host microbiota and host immunity, capable of shaping the clinical outcomes of parasitic infections. 46,48

CLINICAL CASE by Pr. Stephen Allen

- During her holiday in Asia, 36-year-old company executive develops non-bloody, slimy, smelly diarrhea with abdominal cramps and bloating.

- In the second week of the illness, stool microscopy revealed giardiasis and she takes a 10-day course of metronidazole.

- Over the course of the following year in the UK she experiences frequent episodes of similar symptoms, each lasting for a few days and forcing her to stay off work.

- After other illnesses are ruled-out by further investigations and a clinical review, she is diagnosed with post-infectious, diarrheapredominant, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D), a condition that develops in 10% of patients following an acute episode of gastroenteritis.54

- She finds that dietary changes and treatments for IBS-D have little effect and wants to know if she should send a stool sample abroad for microbiome analysis and whether a fecal transplant might help.

- The role of persistent dysbiosis in postinfectious IBS due to parasitic infection and/or drugs used for treatment is poorly understood. More research is needed before this woman’s questions can be answered with any confidence.

EXPERT OPINION

Gut parasite infection is a common cause of disease worldwide, predominantly diarrhea with protozoans such as giardia, Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium, and anaemia with helminths. Equally, gut parasites occur as commensals and may even bring health benefits such as improving resistance to other enteropathogens and preventing allergic and auto-immune diseases. The challenge is to gain a better understanding of the complex interrelationships between different parasites, the intestinal mucosa, gut immune cells and the gut microbiota in order to be able to exploit the benefits while at the same time ameliorating adverse effects of intestinal parasitic infection.