Improvement in insulin sensitivity after faecal microbiota transplant depends on the initial microbiota composition of recipients

Commented article - Adult section

By Pr. Harry Sokol

Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Saint-Antoine Hospital, Paris, France

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Author

Commentary on the original publication by Kootte et al. ( Cell Metab 2017)

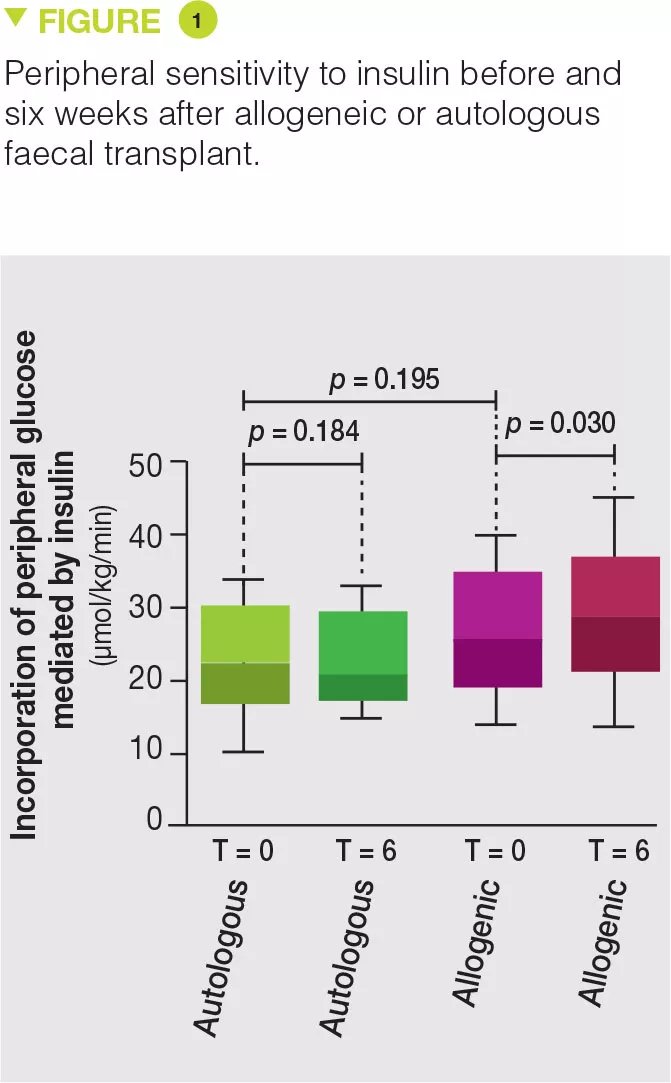

The gut microbiota is involved in insulin resistance although there is limited evidence of a causal link. We compared the effect of faecal microbiota transplant (FMT) from a thin donor (allogeneic) to that of an auto-transplantation (autologous) in male patients with metabolic syndrome. While no metabolic change was observed 18 weeks after FMT, insulin sensitivity was significantly improved at six weeks in the allogeneic FMT group and this was associated with a change in microbiota composition. We also reported changes in plasma concentrations of metabolites, such as γ-aminobutyric acid, and showed that the metabolic response after FMT (defined as the improvement in insulin sensitivity six weeks after FMT) was present in patients with a microbial diversity reduced to basal level. In conclusion, the beneficial effects of FMT from thin donors on carbohydrate metabolism are associated with changes in gut microbiota and plasma metabolites, and can be predicted by the basal microbiota composition of the recipient.[4]

What is already known about the topic?

Obesity and related disorders, such as diabetes, require new therapeutic approaches because the current treatments, including lifestyle changes, and antidiabetic treatments are insufficiently effective in reducing morbidity and mortality. During the last decade, changes in gut microbiota composition have emerged as a potential new therapeutic strategy for improving insulin sensitivity [1]. Several studies have shown that gut microbiota composition is different between thin and obese animals, but also that the microbial composition may reflect impaired metabolic functions, in particular, with a disturbance of ingested food [2]. Finally, these animal studies have suggested a causal link between microbiota abnormalities and metabolic syndrome since the phenotype is transferable by FMT [2]. Although numerous observational studies have suggested correlations between an altered microbiota composition and metabolism in humans, the causality has been difficult to prove. The authors of this study have previously shown in a small pilot study that FMT from thin donors to men with metabolic syndrome induced an improvement in carbohydrate metabolism, together with changes in faecal and duodenal microbiota [3]. Based on these results, the authors have studied the short- and long-term effects of FMT from thin donors on gut microbiota composition in a larger group of men with metabolic syndrome and investigated the pathophysiology of insulin resistance by correlating changes in gut microbiota with several markers of metabolism. In addition, the authors have attempted to identify basal characteristics of the microbiota of recipients in order to explain the improvement in insulin sensitivity in some patients (referred to as metabolic responders) and not in others (non-responders).

Key points

-

FMT from thin donors improves insulin sensitivity in obese patients with metabolic syndrome

-

There is interindividual variability in the response and the latter is transient

-

The improvement in insulin sensitivity is related to changes in plasma metabolites

-

The response to FMT is dependent on initial microbiota composition in patients

What are the main results of this study?

Thirty-eight obese men with metabolic syndrome were included and randomized in the allogeneic (n = 26) or autologous (n = 12) FMT group. FMT was administered by nasoduodenal tube and repeated six weeks later. Eighteen weeks after FMT, no effect was observed on both the microbiota and the parameters of metabolic syndrome. However, six weeks after FMT, the microbiota of the allogeneic FMT group was changed and the metabolic parameters, in particular insulin sensitivity, were improved while no change was observed in the autologous FMT group (Figure 1). In contrast to their previous study, no change in faecal concentration of butyrate was observed [3]. However, allogeneic FMT was associated with an increase in faecal concentration of acetate, as well as changes in the blood level of about 30 metabolites, several of which are involved in the metabolism of tryptophan. In the subgroup of patients who favourably responded to allogeneic FMT, changes were observed in the faecal microbiota, such as, for example, an increase in Akkermansia muciniphila bacterium, and the favourable effects of this bacterium were demonstrated on metabolic syndrome in mice. The authors also highlighted that the basal microbiota composition, as well as a low diversity, were predictive of a good response to FMT.

What are the practical consequences?

Interventions on the gut microbiota, and particularly FMT, are a valid therapeutic approach for metabolic syndrome. Nevertheless, there is high interindividual variability in the response, which may be related to factors from the host, but also from the donor. In addition, the effects are relatively modest with a single FMT and, at best, they are transient. More targeted strategies, such as the use of new generation probiotics (microbiota-derived bacteria) and prolonged administration, are therefore more attractive and are currently being studied.

Conclusion

This interventional study demonstrates that the gut microbiota plays a role in metabolic syndrome and is not just a passive stakeholder. The underlying mechanisms could involve the production of metabolites by the gut microbiota, which modulate the host signalling pathways. Nevertheless, the effects are relatively modest and transient. More targeted strategies, such as the use of new generation probiotics and prolonged administration, are therefore more attractive and are currently being studied.