Functions of the microbiota and its interactions with the host

For a long time, the skin microbiota was considered a potential source of infection. Now we know it to be an important factor in host health2, even if its interactions with the body are only beginning to be understood.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

Staphylococcus epidermidis.

About this article

Reduced colonization by pathogens

Although it remains difficult to define, a “healthy” skin microbiota is generally considered synonymous with a diversified flora and the presence of commensal bacteria.2 This balanced microbiota is thought to help protect against infection, limiting colonization by pathogens. For example, C. acnes, which lives in the sebaceous glands, releases fatty acids from sebum, contributing to the acidity of the skin, which in turn inhibits the proliferation of pathogens.8

Other bacteria secrete bacteriocins and other antimicrobial factors. For example, S. epidermidis releases a protease that destroys S. aureus biofilms, while nasal bacterium, Staphylococcus lugdunensis, produces an antibiotic peptide that acts against many pathogens, including S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.2

Lastly, Corynebacterium striatum modifies the transcriptional program of S. aureus, repressing virulence-related genes and stimulating those associated with commensalism. 6,8 The skin microbiota thus maintains its balance not only by competitive exclusion but also via subtle interactions between microorganisms.6

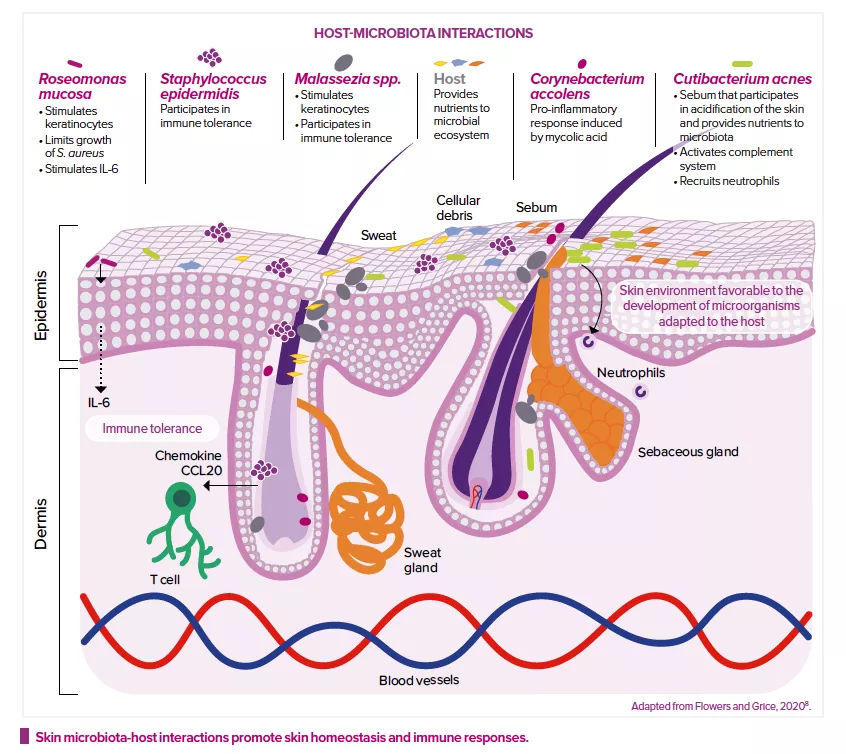

Modulation of the immune system

The skin microbiota also plays a key role in the development and regulation of the innate and acquired immune systems.2 It modulates the expression of innate immune factors (interleukin IL-1α, antimicrobial peptides, etc.) produced by keratinocytes and sebocytes6, and even produces some of these factors itself.

For example, S. epidermidis can, in different situations, either stimulate or reduce inflammation: it inhibits the release of inflammatory cytokines by keratinocytes and the immune responses of injured skin cells; it reinforces the skin’s defense mechanisms against infection by increasing the expression of genes that encode for antimicrobial peptides; and it modulates the expression of skin T cells.2 S. epidermidis promotes tolerance towards the commensal microbiota, while adjusting immune responses to pathogens or those triggered during wound healing.8 Roseomonas mucosa, Malassezia spp. or Corynebacterium accolens can also modulate host and keratinocyte immune responses.8

Lastly, the genetic profile of bacteria also plays a role. Cutibacterium acnes strains from acne-prone skin have genes that encode for virulence factors, which could explain the higher pro-inflammatory activity observed. Conversely, strains from healthy skin, which do not have these factors, are thought to promote the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines.8