Ears, Nose and Throat microbiota: when antibiotics challenge our first line of defense

By disrupting the microbiota in the ears, nose and throat (ENT), antibiotics may leave the door open to opportunistic pathogens implicated in ear and respiratory infections. Their effects could be particularly counterproductive in cases of acute otitis media.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

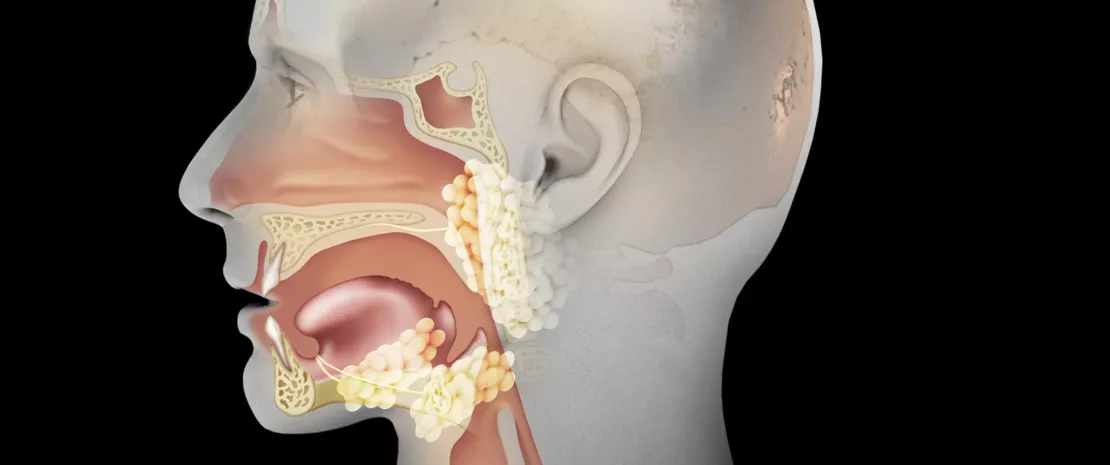

What is commonly referred to as the “ears, nose and throat (ENT) microbiota” is in fact comprised not of one but rather of several microbiota. Antibiotics are likely to act individually on these different microbiota, ranging over the oral cavity through to the pharynx, including inside the sinuses and even the middle ear. This chapter is mainly devoted to the effects of antibiotics on the Upper Respiratory Tract (URT) microbiota, which is an excellent textbook case: the URT microbiota appears to be one of the safeguards of auricular health, yet it is threatened by antibiotics prescribed for this purpose, notably in cases of acute otitis media.

“Within 7 days of antibiotics being administered for URT infections, the incidence of acute otitis media has been shown to increase by a factor of 2.6.”

The URT microbiota, an ally of aricular health?

The URT microbiota is colonized directly after birth by a variety of commensals (Dolosigranulum Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Moraxella, Streptococcus). Mounting evidence suggests that a higher relative abundance of commensal species (Dolosigranulum spp. and Corynebacterium spp.) as well as a greater diversity in the nasopharyngeal microbiota1 are associated with a lower incidence of URT colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis,2,3 three otopathogens implicated in acute otitis media (AOM) .

Antibiotic treatment: much risk for little benefit

Exposure to antibiotics impacts the URT microbiota by decreasing the abundance of protective species and by increasing the abundance of Gram-negative bacteria (Burkholderia spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Comamonadaceae, Bradyrhizobiaceae),4,5 as well as S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis.5 As a result of acquiring antimicrobial resistance, these bacteria, which could not otherwise successfully compete in this niche, are given the opportunity to multiply during treatment to an extent that they may become pathogenic.6 Furthermore, antibiotics are considered unlikely to confer any benefit in most cases of pediatric AOM (the primary reason for prescribing antibiotics to children7) and other URT infections (sore throats or common colds),7,8 due to the frequently non-bacterial nature of these conditions: from 60% to 90% of children with a AOM recover without antibiotics.9,10 Finally, antibiotics lead to gut microbiota dysbiosis that can translate into side effects such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea3,11 (see gut microbiota section).

Expert opinion

In flora hitherto unexposed to antibiotic treatment, there is a harmonious balance between the various commensal bacteria. Disrupting this balance with antibiotics can promote the proliferation of certain bacteria, likely to become pathogenic. In particular, the repeated intake of antibiotics promotes the selection of multidrugresistant bacteria that can no longer be kept in check by the commensal flora, which leads to the more frequent occurrence of infectious complications. It therefore seems essential to preserve the native flora and its natural balance by limiting the use of antibiotics to situations where they are strictly necessary.