Proton pump inhibitors modify gut microbiome

Press review

By Pr. Markku Voutilainen

Turku University Faculty of Medicine; Turku University Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Turku, Finland

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Author

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which are nowadays ones of the most widely used medicines even if about half of the prescriptions lack an evidence-based indication, have a central role in the treatment of peptic ulcer and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. PPIs inhibit acid secretion from gastric parietal cells. PPI-induced hypochlorhydria may increase the risk of infections.

Mishiro et al. investigated the impact of 20 mg daily esomeprazole for 1 month on saliva, periodontal pocket fluid and fecal microbiota in 10 healthy volunteers.[1] Colonic microbiota contained the greatest number of species. Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria were the most abundant species in faeces, whereas Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Fusobacteria were the most common in saliva and periodontal pocket fluid. PPI caused a significant reduction in the diversity of salivary microbiota. Streptococci, which are predominantly found in the upper gastrointestinal tract, were increased in faeces and also in saliva and periodontal pocket after PPI treatment.[1]

Antibiotics and acid-suppressive medications cause dysbiosis. Stark et al. performed a retrospective study with 333,353 US children.[2] PPI prescriptions were associated with obesity, each additional antibiotic class increased the risk of obesity, and each additional 30-day prescription of acid-suppressive medication strengthened the association with obesity.

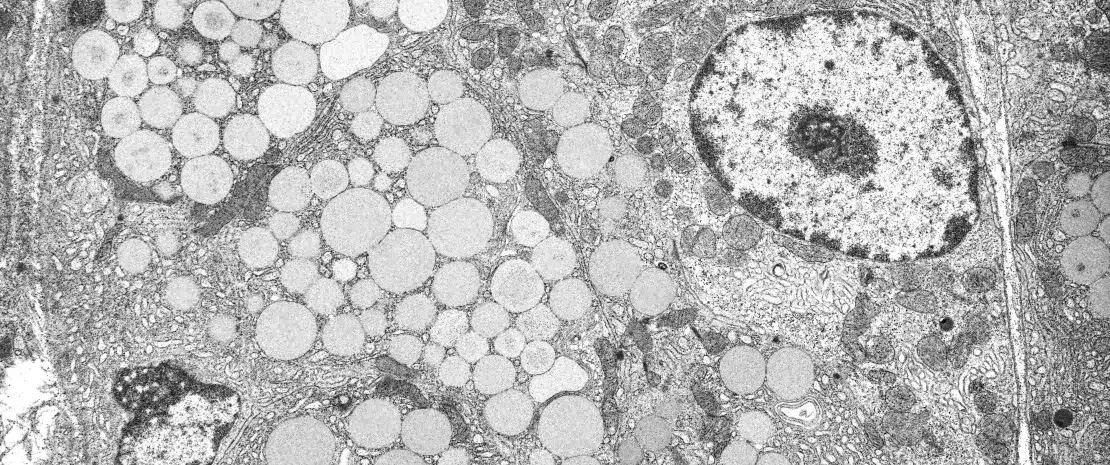

Mailhe et al. examined the gastrointestinal microbiota composition of 6 patients who underwent gastroscopy and colonoscopy.[3] Samples were obtained from stomach, duodenum, ileum, and colon. Culturomics was performed with mass spectometry MALDI-TOF and metagenomics targeting the V3-V4 region in the 16S rRNA. In all, 368 bacterial species were observed (37 new species): 110 from the stomach, 106 from the duodenum and 235 from the left colon. The upper gut contained less aero-intolerant species and less rich microbiota compared with the lower gut. Three patients used long-term PPI treatment; their gastric pH and bacterial diversity were higher compared with those not using PPI.

Investigators from Cleveland, have reviewed the impact of PPIs on gut microbiome [4]. The main consequence of PPI treatment is the increase in gastric pH. PPI treatment may lead to excess Streptococcus gastric colonisation, which may cause dyspeptic symptoms. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth risk is moderately increased during PPI treatment.[4] PPI and antibiotics increase Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) risk. PPI treatment may also increase spontaneous bacterial peritonitis risk in hepatic cirrhosis. A statistical association between PPI use and the incidence of Salmonella and Campylobacter infections has been reported.

Observational studies reporting associations between PPI use and side effects do not necessarily prove causal relationship. PPI users are often sicker than non-users, which could partially explain the increase of side effects. Anyhow, PPIs should be used only on evidence-based indications with lowest effective doses and should be stopped when the treatment response has been achieved.