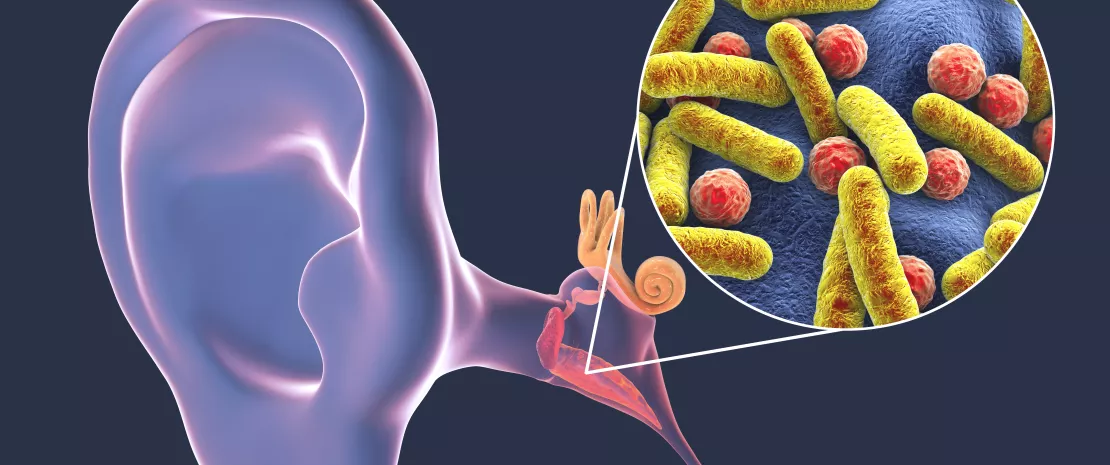

Does the nasal microbiota modulate the risk of otitis?

A study combining 16S rRNA sequencing and large-scale bacterial culture (“culturomics”) has documented the nasal microbiota characteristics associated with the ear and nose health of indigenous Australian children (2-7 years), a population at high risk of otitis.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

While otitis is common in childhood, (sidenote: Les enfants aborigènes australiens seraient 5 fois plus à risque d’otite sévère de l’oreille moyenne que les enfants australiens non aborigènes. Gunasekera H, Knox S, Morris P et al. The spectrum and management of otitis media in Australian indigenous and nonindigenous children: a national study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007 Aug;26(8):689-92. ) . The problem is that studies seeking to characterize the microorganisms associated with the disease in these populations have so far looked for known otopathogens (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis) or have mainly used culture techniques that do not reveal the presence of microorganisms that are difficult to cultivate.

By analyzing the nasal microbiota of 101 indigenous Australian children using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and a more extended bacterial culture, the researchers studied the associations between nasal microbiota composition and the children’s ear and nasal health.

Moraxella, a marker of previous otitis?

They found a greater relative abundance of Moraxella in children who had previously had an ear infection. This was so even in children who were free of otitis at the time of the analysis and may be due to a lasting remodeling of the nasal microbiota following a previous case of otitis. Moreover, the abundance of Moraxella in the nasal microbiota was negatively correlated with that of Staphylococcus, a bacterial genus found in greater abundance in children with no infectious nasal discharge. In vitro data suggest that certain species of Staphylococcus may inhibit Moraxella, which could explain the negative correlation observed.

A protective duo of microorganisms?

Furthermore, in the children not suffering from an ear condition at the time of the study, a positive correlation was observed between Dolosigranulum and Corynobacterium. This correlation was also found in children with no infectious nasal discharge, leading the authors to consider this co-colonization as potentially protective against pathogens such as S. pneumoniae and guaranteeing the health of the upper respiratory tract and ear.

Towards the identification of new otopathogens

In contrast, Ornithobacterium was found in greater abundance in children with serous otitis than in the children who had never had otitis. It may thus be a new otopathogen. Its presence was correlated with that of two other bacterial genera, Dichelobacter and Helcococcus, whose effects on nasal and ear health have yet to be defined.

This study combining 16S rRNA sequencing and culturomics was the largest ever conducted on indigenous populations. It has described associations between the nasal microbiota and ear and nasal health, identifying potential synergies (and antagonisms) between microorganisms, and new otopathogenic candidates, which will now have to be studied in greater detail.