Adaptation of commensal Escherichia coli in the intestinal tract of young children with cystic fibrosis

Commented article - children section

By Pr. Emmanuel Mas

Gastroenterology and Nutrition Department, Children’s Hospital, Toulouse, France

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

About this article

Comments of the original article by Matamouros et al. (PNAS 2018)

The mature human gut microbiota is established during the first years of life, and altered intestinal microbiomes have been associated with several human health disorders. Escherichia coli usually represents less than 1% of the human intestinal microbiome, whereas in cystic fibrosis (CF), greater than 50% relative abundance is common and correlates with intestinal inflammation and faecal fat malabsorption. Despite the proliferation of E. coli and other Proteobacteria in conditions involving chronic gastrointestinal tract inflammation, little is known about adaptation of specific characteristics associated with microbiota clonal expansion.

This study shows that E. coli isolated from faecal samples of young children with CF has adapted to growth on glycerol, a major component of faecal fat. E. coli isolates from different CF patients demonstrate an increased growth rate in the presence of glycerol compared with E. coli from healthy controls, and unrelated CF E. coli strains have independently acquired this growth trait. Furthermore, CF and control E. coli isolates have differential gene expression when grown in minimal media with glycerol as the sole carbon source. While CF isolates display a growth-promoting transcriptional profile, control isolates engage stress and stationary-phase programmes, which likely results in slower growth rates. These results indicate that there is selection of unique characteristics within the microbiome of individuals with CF, which could contribute to individual disease outcomes.[1]

What is already known about this topic?

The main digestive issue in cystic fibrosis (CF) is exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. This is present in 85% of cases and requires supplementation with pancreatic extracts. Despite this supplementation, fat malabsorption may persist. The proportion of Escherichia coli (E. coli) in the human gut microbiome is usually less than 1% but may reach up to 70-80% in patients with CF. There is clonal expansion within a given patient, but the strains are different between patients, which suggests an adaptation of E. coli to its environment. Some strains of E. coli are involved in gut inflammation and colorectal cancer (CRC). According to recent data, digestive inflammation, dysbiosis, or an increased risk of CRC may be associated with CF.

The authors have assumed that a selection of E. coli strains exist in patients with CF, as these strains are capable of surviving in a gut environment containing excess fat and abnormal mucus.

What are the main results of this study?

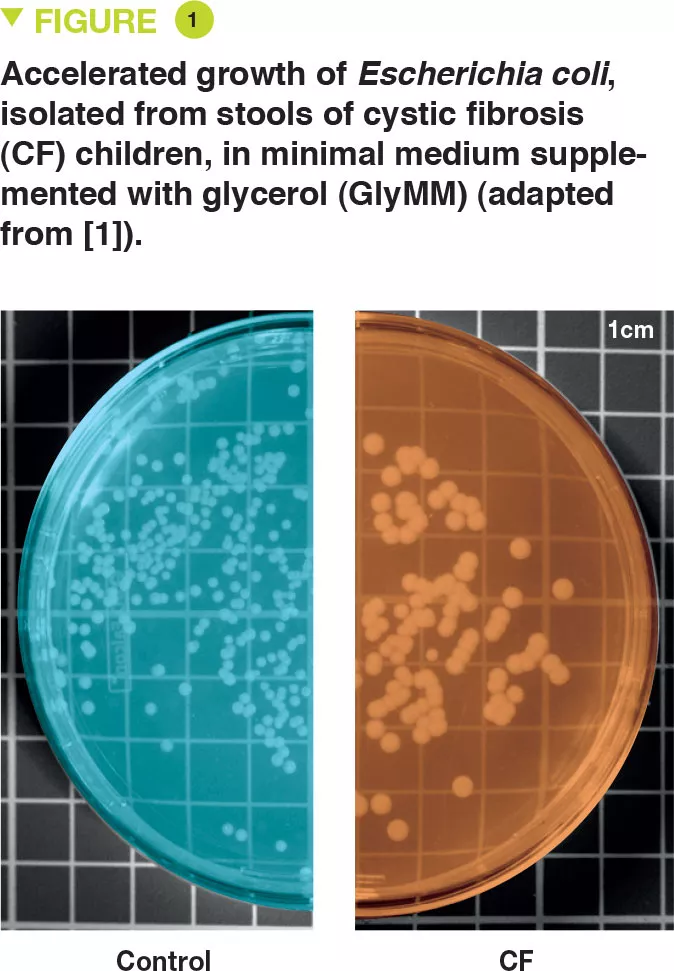

E. coli was isolated from the stools of six young children with CF and two controls. The authors assessed the growth of these bacteria in a minimal medium for which the only source of carbon was glucose (GluMM) or glycerol (GlyMM) supplementation. E. coli growth was faster in GlyMM plates for strains isolated from CF children compared to those isolated from controls (Figure 1). These differences were not observed under anaerobic conditions. Since the gut environment is essentially anaerobic, oxygen may play an important role, and in the vicinity of the epithelium, the oxygen gradient is minimal.

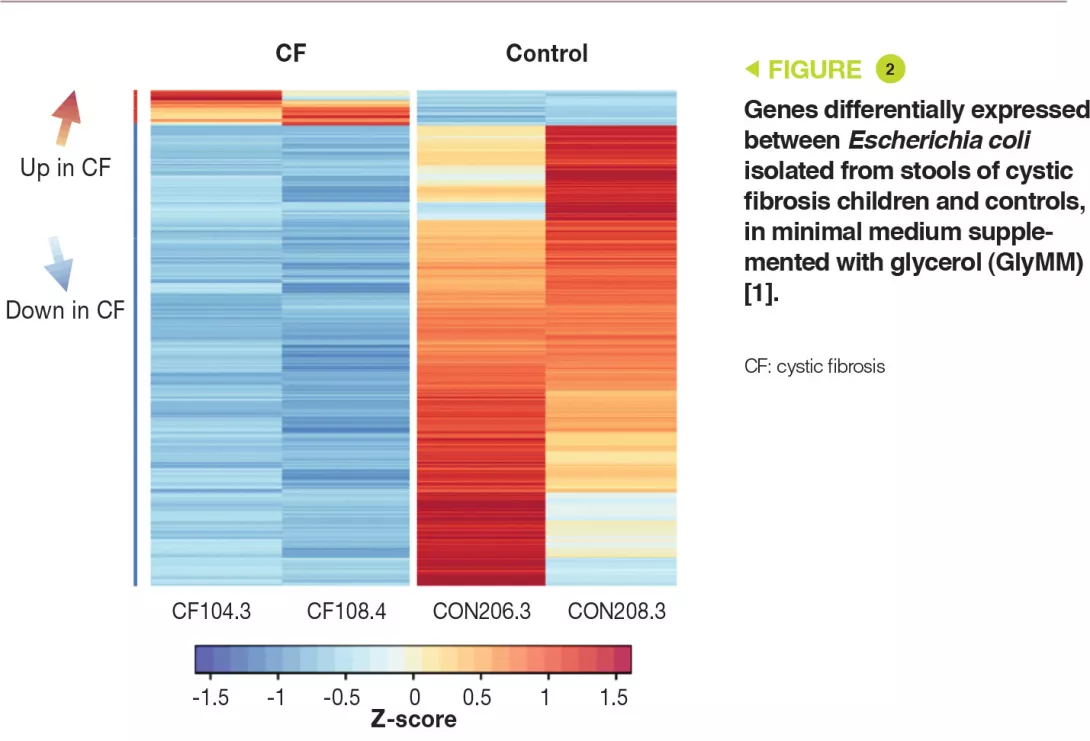

Genetic analysis has shown that the E. coli strains were distinct. In addition, the eight isolates had more than 11,000 SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) present in one or more children with CF, which were absent in controls. Transcriptomic analysis (RNA-sequence analysis) in the GluMM or GlyMM medium was performed on isolates from two CF children and two controls. These isolates were selected due to their growth in GlyMM medium and their position within the phylogenetic tree. Among the genes expressed differentially, 213 were overexpressed (glycerol absorption and metabolism) and six were under-expressed (glucose cell transport) in GlyMM medium, in a similar way in both CF children and controls. In GluMM medium, only 20 genes were expressed differentially between CF children and controls, compared to 405 genes in GlyMM medium (377 genes were not induced in CF children) (Figure 2). The genes that were under-expressed in CF in GlyMM medium encode proteins involved in stress, acid resistance, and biofilm formation; the genes overexpressed in CF or under-expressed in controls encode proteins involved in growth mechanisms. In CF, the increased growth in GlyMM medium is not related to metabolic reprogramming, but to a loss of growth inhibition and a stress response.

Key points

-

Gut dysbiosis may be observed in CF. In particular, there is a significant increase in E. coli levels.

-

Due to fat malabsorption, intestinal glycerol levels are increased. In CF, selected strains of E. coli are adapted to these conditions with differentially expressed genes and a loss of growth inhibition.

What are the practical consequences?

This study leads to an understanding of the mechanisms involved in CF-associated dysbiosis with regards to E. coli. In order to correct this dysbiosis and limit, at least in part, gut inflammation, it is important to optimise the absorption of intestinal fat to ensure reduced glycerol levels.

An improvement in the intestinal barrier, especially with regards to mucus for this disease, may also reduce the availability of oxygen necessary for the growth of these E. coli strains.

Conclusion

In CF, the high intestinal level of glycerol due to fat malabsorption results in E. coli adaptation with clonal proliferation. Understanding these mechanisms may allow us to develop new therapeutic approaches and improve patient management.