Female anatomy, microbiotas and intimate hygiene

The difference between vulva and vagina? (You don't get it ?). Intimate hygiene? (Still don't get it?)... When you ask women about these subjects, they’re often evasive. Practical lesson in anatomy and good practices.

- Learn all about microbiota

- Microbiota and related conditions

- Act on your microbiota

- Publications

- About the Institute

Healthcare professionals section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

We thought the younger generations had been successfully liberated by the feminist struggles of the 2000s, but they are proving even less comfortable than their elders when talking about female genitalia. And while forty-somethings scramble for intimate deodorants, under the influence of adverts promoting the freshness of their nether regions, the next generation, more mindful of their image, are turning to cosmetic procedures, like (sidenote: Vulvoplasty Plastic surgery of the vulva, to increase or reduce the size or volume of the labia majora. ) 1. Each generation has its own unique relationship with intimacy, it would seem. Regardless, the hygiene and health of this fragile body area should concern us at all ages... hence these few cheeky reminders, to lift the veil on any taboos.

A little Anatomy

The female genitalia is both a terra incognita in terms of anatomy and a taboo in terms of conversation, including among women. So much so that health professionals struggle to understand their patients’ ailments due to insufficiently clear explanations, and/or because they confuse the vulva (external part of their genitalia) with their vagina (internal part)1.

In short:

the vulva is on the outside and the vagina within!

The vulva

is made up of a set of tissues visible on external examination1:

- part of the pubic mound (also called mons pubis or mons Venus), which is the fleshy, hairy area covering the pubic bone,

- the clitoris, linked to sexual pleasure, which is the female counterpart of the male foreskin,

- the labia majora, which are the larger protective outer folds,

- the labia minora, which are located inside the labia majora and comprise numerous sebaceous glands,

- and the vulval vestibule, which is the area between the labia minora, where the vaginal entrance is found, and the urethral meatus, just above it (orifice of the urinary system).

The skin covering the pubic mound and labia majora has sebaceous glands1 that produce a protective hydrolipidic film1,2.

The vulva also has glands (Bartholin’s glands, Skene’s glands) that lubricate the labia minora and vulval vestibule during intercourse1.

The vagina

is a cavity about ten centimeters in length that is not visible from the outside.

- At its lower part, it communicates with the exterior, at the vulva, or more specifically the vulval vestibule;

- at its apex, it leads to the cervix1.

The vagina can accommodate tampons and menstrual cups during menstruation, a partner’s penis during intercourse, your favorite sex toy... and your gynecologist’s speculum at medical consultations!

Now that we’ve come this far, we might as well explain all the other orifices. From front to back, the female genitals include three openings, in this order:

- the urinary meatus, connected to the bladder (which stores urine) by a canal called the urethra (which allows urine to be evacuated outside the body during urination)2,

- then the entrance to the vagina (reproduction)

- then the anus (stools).

We speak also of:

designating the area surrounding the anus;

designating the large area formed by the vulva and the perianal area (in other words, the entire crotch area).1

Female intimate microbiotas

Our intimacy is no exception; like other organs, it is home to several microbiotas, which are:

Let’s start with the vulvar microbiota. You’d think we know it well, given that it’s on the outside. And yet, data on this subject is scarce1,3. The few studies carried out pay lip service to the possible presence of various bacteria (Lactobacillus, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus and Prevotella) and yeast-like fungi1,3.

It can clearly be a matter of vulvar microbiotas in the plural, depending on the area of the vulva: microbiota of the pubic mound, microbiota of the labia majora, microbiota of the labia minora, etc...3

One thing seems certain, however, diversity is the name of the game, not only:

- in each woman’s vulvar microbiota, where an abundance of (sidenote: Microorganisms Living organisms too small to see with the naked eye. This includes bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea, protozoa, etc., collectively known as ’microbes’. Source: What is microbiology? Microbiology Society. ) coexist, but also

- between two women (no single listed species is found in all women)1.

When it comes to the vaginal microbiota (or vaginal flora), the opposite is true. In the vagina, lactobacilli (in particular Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus iners, Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus jensenii) generally reign supreme and maintain local acidity by producing lactic acid1,4.

This acidic pH, from 4.0 to 4.5, keeps (sidenote: Pathogens A pathogen is a microorganism that causes, or may cause, disease. Pirofski LA, Casadevall A. Q and A: What is a pathogen? A question that begs the point. BMC Biol. 2012 Jan 31;10:6. ) at bay, as do the hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins produced by these same lactobacilli to overcome the most recalcitrant pathogens.

The urinary microbiota has long been considered sterile. This is a mistake, since urine contained in the bladder also has a microbial ecosystem. Although the urinary microbiota is quite distinct from its close neighbors (anal, vaginal and vulvar microbiotas), it shares certain microorganisms with them5. It is also much less densely populated, and often dominated by a single bacterial type. These include mainly lactobacilli, but also Gardnerella, Streptococcus and Corynebacterium6.

Finally, the perianal microbiota is a reflection of our very rich gut microbiota, particularly in the colon: when we pass stools, intestinal bacteria come into contact with this area and can take up residence there1.

1 in 5 Only 22% of women claim to know exactly what the “vaginal microbiota” is (+2 points vs. 2023).

Microbiotas so close as to be exchanged

Vulvar, vaginal and perianal microbiotas evolve over time. For example, the vaginal microbiota is influenced by age, sex hormones and external factors such as pollution, stress, antibiotics, etc4. Imbalances can occur: after menopause, the drop in estrogen leads to a loss of lactobacilli and therefore a rise in pH, resulting in frequent vaginal dysbiosis7. As for the anal microbiota, it depends above all on diet and stress: excessive anxiety induces an inflammatory response that favors the development of pathogenic bacteria in the digestive tract... which end up in the perianal area1.

The proximity of the urinary, vaginal and anal orifices also explains possible “exchanges” of flora between the 3 microbiotas in these 3 areas... and the possible invasion of the vaginal microbiota by digestive Escherichia coli that may have ventured beyond the perianal area1.

Bacterial Vaginosis

Antibiotics

Excessive hygiene, over-waxing, too-tight clothing… a losing combo

Paradoxically, inappropriate intimate hygiene practices can actually encourage exchange and imbalance. Washing the vulva too aggressively (with unsuitable products) or too frequently (more than once a day) can quickly damage the skin barrier function in this very fragile and reactive area. Water alone can be enough to dry it out and expose it to itching and burning8. And the perfumed soaps, intimate sprays, lubricants, deodorants, etc. that some women self-prescribe in an attempt to treat odors, itching, pain and dryness are counterproductive4.

Also to be avoided:

Products not intended for intimate hygiene (hand sanitizers, baby wipes, oils, shaving cream and body lotions). More women than you might think use them differently from their intended purpose: 41.6% of women in one study admitted using baby wipes for vulval cleansing... and 2.1% for internal vaginal cleansing4!

Let’s not forget:

the vagina has no need to be cleansed!

Another common error: waxing or shaving the entire vulva1,9. This is a fashion phenomenon that concerns 84% of premenopausal American women, for 2/3 of whom it is a daily or weekly routine. Often justified on hygienic grounds, the reverse is actually true: it creates lesions that make it easier for bacteria and viruses to enter. Alterations in the vaginal microbiota have in fact been observed in women opting for full vulva hair removal9.

Finally, wearing very tight, synthetic clothing seems also to encourage the development of pathogens (a warmer, more humid environment), resulting in more frequent itching and urogenital problems1.

Better informing women

1 in 2 52% of women surveyed said they had never received information on proper intimate hygiene practices, and 25% said they had only been informed once by their health practitioner.

Why is there such a gap between practices and recommendations? There are undoubtedly many reasons for this:

- too few women are informed by their doctors about good practices: 52% of women surveyed said they had never received such information, and 25% had only been informed on one occasion by their health practitioner17;

- the frequent confusion between vulva and vagina means messages are misunderstood;

- the stupidest myths are often those that stick most1.

This problem is all the more important when you consider that the vulva is the first line of defense in a woman’s genital system10.

What women know (and don't know) about their vaginal microbiota

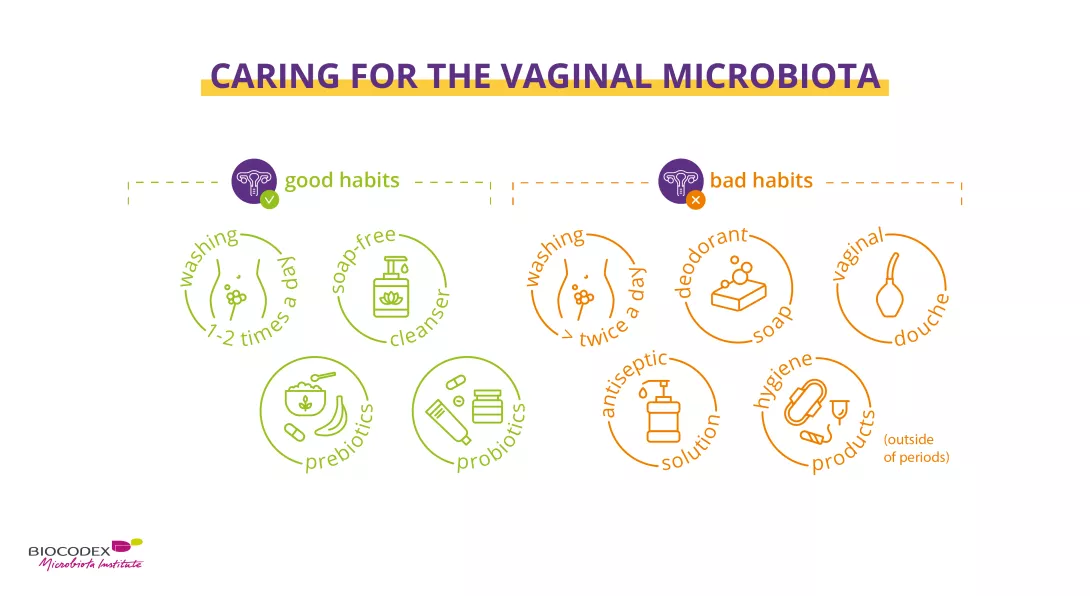

(Real!) good hygiene practices

The right way to preserve the microbiota and the delicate protective hydrolipidic film of female genitalia. A routine that respects the balance of the vulva, with products adapted to the age and specific needs of each woman.

In all cases, there are 3 main immutable principles10:

- external washing only (= vulva, no vaginal douching), from front to back (vulva then anus)

- without a washcloth (which may contain bacteria), but with clean hands,

- once a day. Only women suffering from frequent diarrhea can justify more frequent external washing (due to more frequent bowel movements). Or during menstruation, when you may need to wash the intimate area a second time during the day.

Washing with water alone can dry out the skin and aggravate itching10. It’s best to use a mild, soap-free cleanser that respects the vulvar microenvironment and maintains the balance of its microbiota1. And that’s all. You can be absolutely sure that less is more on this delicate part of the body.

Finally, here are a few additional recommendations to help you adopt the right practices throughout the day10:

- at night, avoid wearing underwear;

- when you get out of the shower (preferable to a bath), dry yourself thoroughly with your own towel, without rubbing but gently dabbing your crotch area;

- when dressing, opt for cotton rather than synthetic undergarments, avoid regular use of panty liners, prefer loose-fitting clothes, replace tights with stockings if possible;

- when using the toilet, wipe from front to back (to avoid bringing anal bacteria to the vulva) with unscented and ideally uncolored paper;

- Here too, it is important to respect the main principles of intimate hygiene: external washing only; with your hands; once a day10.

- after sexual relations (protected!, unless you’re sure your partner isn’t carrying an STI), take time to urinate if you’re prone to cystitis;

- during menstruation, do not use scented sanitary pads, and change your sanitary pad or tampon regularly10.

Probiotics and prebiotics

Healthy vaginal microbiota depends on good intimate hygiene. But sometimes that’s not enough, and a little help may be needed to boost the good bacteria in your microbiota, with:

Probiotics

Probiotics, living microorganisms which, when administered in appropriate quantities, have beneficial effects on the host’s health11,12. Administered orally or vaginally, they can help restore vaginal flora, improve symptoms and reduce the risk of various vaginal infections recurring, form puberty to menopause13.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics, non-digestible dietary fibers with positive health effects used selectively by beneficial microorganisms in the host microbiota12, 14. In other words, the preferred foods of probiotics to help them thrive. For example, female prebiotics boost vaginal lactobacilli and help normalize vaginal acidity15,16.

What is the difference between prebiotics, probiotics and postbiotics?

To sum up...

Female genitalia are made up of:

- the vulva (external part)

- and the vagina (the cavity that connects the vulva to the uterus, into which you can insert a tampon when you have your period).

The genitalia are home to several microbiotas: the vulvar microbiota in which diversity is key, the vaginal microbiota dominated largely by lactobacilli, the urinary microbiota which is sparsely populated (for a long time, urine was wrongly thought to be sterile), and a very rich perianal microbiota (contact with stools).

The proximity of the urinary, vaginal and anal orifices explains why “exchange” of flora between the microbiotas of these areas is possible, particularly in the case of inappropriate intimate hygiene: too aggressive washing, waxing or shaving of the entire area, wearing clothes that are too tight, etc.

Due to a lack of information, many women do not adopt the right practices to protect their microbiotas. But it’s not too late – so bite the bullet and talk about it with your doctor!

If your vaginal microbiota is flagging, prebiotics and probiotics can help you restore a balanced vaginal flora.

2. Biology of the Kidneys and Urinary Tract. MSD Manuel. https://www.msdmanuals.com/home/kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/biology-of-the-kidneys-and-urinary-tract

6. Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L. Female urinary microbiota. Curr Opin Urol. 2017 May;27(3):282-286.

7. Auriemma RS, Scairati R, Del Vecchio G et al. The Vaginal Microbiome: A Long Urogenital Colonization Throughout Woman Life. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 Jul 6;11:686167.