Taurine “energizes” the gut microbiota against pathogens

When faced with infection, the host produces taurine, a nutrient that feeds the microbiota and helps eliminate pathogens. As a result, taurine increases long-term resistance to subsequent infection.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. The immune system applies this saying to the letter. Its adaptive responses to pathogens allow for a swifter and more robust defense against subsequent infections. What if the same were true of the gut microbiota? Could initial infections allow it to develop an optimal antimicrobial function, thus increasing resistance to host colonization? So suggest the researchers in this study.

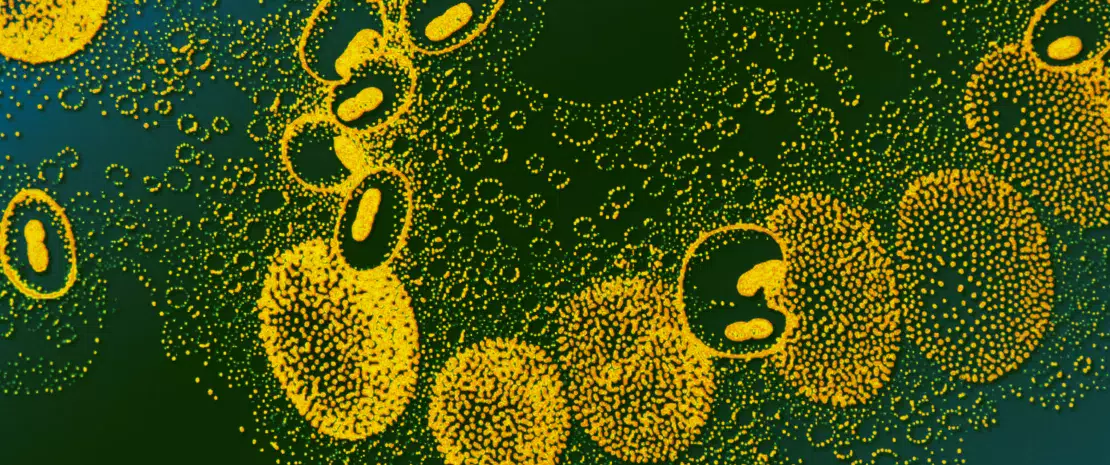

Metaorganism memory

The experiments in question involved the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kpn). In orally infected mice, the bacterium is detected transiently in the lumen of the colon and then disappears from the feces. The only exception is when the mice have received a broad-spectrum antibiotic (streptomycin) beforehand, in which case their fecal Kpn load remains high. Colonization of the host by this pathogen thus seems to be regulated by the microbiota. With this point confirmed, a long series of experiments allowed the researchers to progressively elucidate the mechanisms by which a transient infection leads to what they call a long-term “metaorganism memory”. The latter is based on the interdependent and combined functions of the host and its microbiota.

Bile acids involved

Following infection, the host’s liver sees increased production of bile acids. Microbial groups in the gut microbiota that are capable of using these acids (particularly taurine) via anaerobic respiration multiply as a result. They convert taurine into sulfide, an inhibitor of aerobic cell respiration. Many pathogens depend on aerobic respiration to survive. Without it, they die, limiting host colonization. On the other hand, sequestering sulfide favors invasion by pathogens. Interestingly, the intake of exogenous taurine has the same effects as an infection: multiplication of bacteria capable of metabolizing it, reinforcement of resistance to colonization, etc.

Resistance to colonization: questions and hopes

However, many questions remain. For example, what signals trigger increased bile acid synthesis following infection? Does the host immune system work alongside the microbiota to promote resistance to colonization following infection? In any case, with antibiotic resistance worryingly on the increase, using bacterial metabolites to fight infection–rather than bacteria themselves–provides a reassuring alternative. Moreover, this strategy has another clear advantage: therapies based on bacteria (such as fecal transplant) face the problem of inter-individual heterogeneity, whereas more “universal” microbial metabolites should respond to much broader targets.