Involvement of E. faecalis in alcoholic hepatitis

The gut bacterium E. faecalis migrates to the liver in the presence of alcohol and can produce a toxin that aggravates alcoholic hepatitis. A bacteriophage specifically targeting this bacterium eliminates inflammation and hepatic lesions.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

Alcoholic hepatitis is the most severe form of alcoholic liver disease and is associated with a mortality rate of 20 to 40% within 1 to 6 months. Although it is known that the gut microbiota can promote ethanol-induced liver diseases in mice, the microbial factors responsible for this process remain poorly understood. Hence the interest in the results published in Nature on the role of the microbiota in transmission and progression of this disease.

Cytolysin-secreting E. faecalis

The research shows that patients with alcoholic hepatitis exhibit a specific fecal microbial composition, namely having 2,700 times more Enterococcus faecalis, a bacterium found in the stools of 80% of patients. However, certain “cytolytic” types of these bacteria produce an endotoxin called cytolysin which acts against eukaryotic cells as well as against Gram-positive bacteria. The presence of cytolytic E. faecalis bacteria seems to be correlated to the severity of the liver disease and patient mortality.

From cytolysin to hepatic lesions

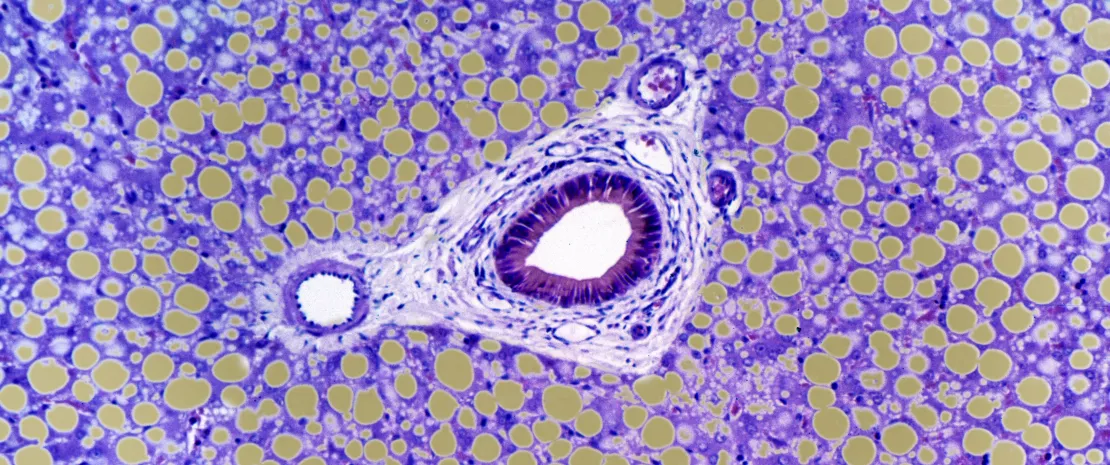

Gavage of mice subjected to a high ethanol intake diet (or to a control isocaloric diet without ethanol), with either cytolytic or non-cytolytic strains of E. faecalis, confirmed that cytolytic E. faecalis induced more hepatic lesions, steatosis and inflammation, and led to a more rapid death. This bacterium was also found in the livers of all mice subjected to a regimen with alcohol, but not in the liver of the control mice, suggesting that ethanol is required for translocation of E. faecalis from the gut to the liver.

A protective bacteriophage

The researchers then studied the therapeutic effects of a bacteriophage targeting cytolytic E. faecalis in mice receiving gavage with strains of E. faecalis responsible for hepatic steatosis. The bacteriophages reduced cytolysin levels in the liver of the rodents and eliminated their ethanol-induced hepatic lesions. The researchers then studied mice colonized with bacteria from stools of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Administration of bacteriophages suppressed the onset of hepatic lesions and steatosis, and led to a decrease in the content of Enterococcus.

A future treatment?

These results not only established a link between the cytolytic E. faecalis bacterium and the severity and mortality rate of alcoholic hepatitis, they also showed that a bacteriophage can target the bacterium specifically, and so provide an alternative to antibiotics. Nevertheless, clinical studies are still required to prove the validity of cytolysin as a biomarker in human subjects, and to confirm that bacteriophages represent a safe and effective therapeutic approach.