From gut dysbiosis to urinary tract infection

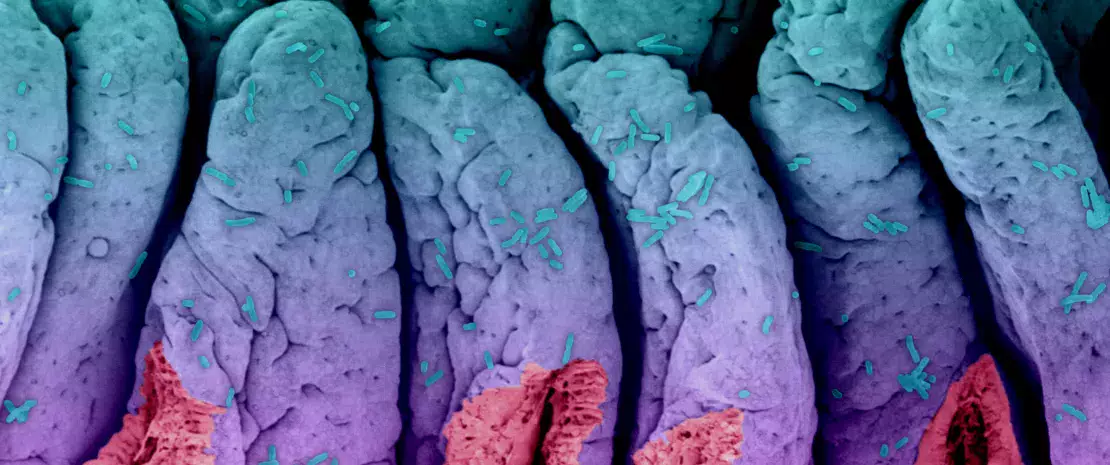

A gut-bladder axis plays a role in the recurrence of urinary tract infections via gut dysbiosis and an inefficient immune response to bacterial colonization of the bladder.

Further details below.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

Common and recurrent. This is the profile of urinary tract infections, which tend to affect the same women, 20% to 30% of whom see the infection return up to six times, or even more, per year. Since the gut acts as a reservoir of pathogenic bacteria that travel up the vulva, researchers have been interested in the potential existence of a “gut-bladder” axis, whereby gut dysbiosis is linked to susceptibility to recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs).For women suffering from rUTIs is there a specific dynamic in, and between, the gut and bladder? Are microbiota-mediated immunological differences linked to this susceptibility?

To answer this question, a one-year longitudinal clinical study was conducted on 15 women with a history of rUTIs and 16 healthy women.

Gut dysbiosis and inflammation

The results showed that women with a history of rUTIs had a less diverse gut microbiota, with more Bacteroidetes, and fewer Firmicutes and butyrate-producing bacteria such as Blautia, which are known to regulate inflammation. In fact, blood tests indicate that women susceptible to infection present characteristics of low-grade inflammation. This suggests that susceptibility to rUTIs is partly mediated by a gut-bladder axis, via gut dysbiosis and altered systemic immunity.

20%-30% of women diagnosed with an UTI will experience recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs).

The role of E. coli

24 urinary tract infections were reported during the study, all in the rUTI group, and in 82% of the cases, they were caused by E. coli.

However, the dysbiosis observed in the rUTI women did not seem to affect the dynamics of this bacterium: the E. coli populations in the gut and bladder were comparable between the two groups, both in terms of relative abundance and phylogroups. However, no symptoms of urinary tract infection occurred in the healthy controls, suggesting that they alone manage to eliminate E. coli from their bladders. Another finding was that the E. coli strains that cause UTIs often colonize the gut persistently, without being permanently eliminated by repeated exposure to antibiotics. In other words, antibiotics may cure UTIs in the short term by eliminating E. coli from the bladder, but would not protect against recurrences over the long term caused by residual E. coli in the gut.

This raises the question of whether prescribing antibiotics is worthwhile, especially since they may exacerbate gut dysbiosis and the resulting inflammation. Instead, potential microbiota alternatives may be the key to restoring a healthy bacterial community in the gut.

Recommended by our community

"i found it interesting!!" -@BevisHTR25 (From Biocodex Microbiota Institute on X)