Dysbiosis-related infections of the lower genital tract

Unlike the urinary microbiota and many other microbiotas, the vaginal microbiota, when healthy, has low diversity and is mostly dominated by a few lactobacilli. A dysbiosis where lactobacilli lose their predominance has been linked to infections of the lower genital tract (bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis).

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

Sections

Candida albicans

About this article

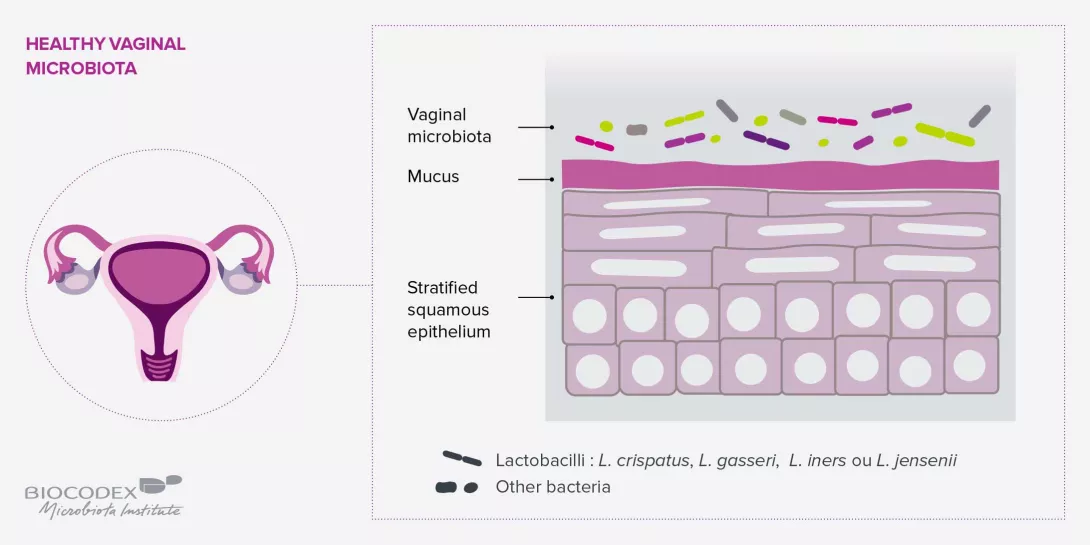

A HEALTHY VAGINAL MICROBIOTA: LOW DIVERSITY AND DOMINATED BY LACTOBACILLI

The vaginal microbiota consists mainly of lactobacilli with a protective role. Despite considerable variability among women, in general, five types of community have been categorized, depending on whether they are dominated by L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners or L. jensenii, or have few or no lactobacilli and a significant quantity of strict anaerobic bacteria (Megasphera, Prevotel- la, Gardnerella and Sneathia) known to be characteristic of bacterial vaginosis.8

Therefore, while a high number of microbial communities is usually an indicator of health for several microbiotas (digestive microbiota, etc.), the vaginal microbiota is balanced when it has low diversity and is dominated by one or a few species of lactobacilli. In women of childbearing age, hormones promote the proliferation of lactobacilli. Estrogen levels induce the deposition of large amounts of glycogen, the main source of energy for lactobacilli, on the vaginal walls.8 From adolescence to the menopause, high estrogen levels promote colonization of the vagina by lactobacilli which metabolize glycogen, produce lactic acid and maintain intravaginal health by lowering the pH level.

the vaginal microbiota is balanced when it has low diversity and is dominated by one or a few species of lactobacilli.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS: WHEN G. VAGINALIS DRIVES OUT LACTOBACILLI

Despite more than sixty years of re- search, the etiology of BV remains unknown. Nevertheless, research seems to point more and more to the dysbiosis theory according to which dominant lactobacilli are replaced by polymicrobial flora derived from numerous bacterial genera (Gardnerella, Ato- pobium, Prevotella, etc.). G. vaginalis is in effect present in 90% of symptomatic subjects and 45% of normal subjects, whereas Lactobacillus sp. is found in 70% of apparently healthy subjects and 40% of symptomatic subjects.9 Consequently, G. vaginalis has been suspected of being the main pathogen in BV. However, there is long-standing disagreement in this regard, since this virulent bacterium has also been found in virgin girls and in sexually active wo- men with normal vaginal microbiota; in other words, colonization by G. vaginalis does not always lead to BV.10

An explanation recently put forward may settle the debate: there is not one, but at least thirteen, different species of the genus Gardnerella, some of which may not be pathogenic. A mechanism for the development of the dysbiosis has even been suggested:10 G. vaginalis, transmitted sexually, spreads itself among healthy vaginal lactobacilli, such as L. crispatus, initiating the formation of a biofilm, a structure that further protects the pathogen from the hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid secreted by the lactobacilli. By reducing the redox potential of the vaginal microbiota, G. vaginalis gradually reduces the lactobacilli population in favor of strict anaerobic bacteria such as P. bivia and A. vaginae. G. vaginalis and P. bivia seem to facilitate each other’s development, the former providing amino acids to the latter and the latter ammonia to the former. Lastly, both pathogens produce an enzyme that destroys the mucus in the vaginal epithelium, facilitating the adhesion of different bacteria associated with BV, such as A. vaginae, and potentially causing a polymicrobial infection.

The vaginal microbiota also plays an important role in maintaining vaginal health and protecting the host against the acquisition and transmission of sexually transmitted infections.

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS: A PROLIFERATION OF CANDIDA

Vulvovaginal candidiasis could be linked to an imbalance of the vaginal microbiota together with a proliferation of the fungus Candida, including C. albicans in 80%-92% of cases,11 and to a lesser extent C. glabrata, C. tropi- calis, C. parapsilosis and C. krusei.12 Exposure to antibiotics, whether local or systemic, is thought to be one of the main factors leading to vulvovaginal candidiasis.13 The reduction of certain bacterial species, lactobacilli or not, that control the replication and virulence of Candida yeasts apparently allows the Chlamydia tractomatis fungi already present in the vagina to multiply and induce infection. Future studies involving new sequencing technologies are needed to characterize in further details the interaction between vaginal microbiota, these yeasts and the occurrence and recurrence of vulvovaginal candidiasis.

HEALTHY VAGINAL MICROBIOTA: A SAFEGUARD AGAINST STIS

The vaginal microbiota also plays an important role in maintaining vaginal health and protecting the host against the acquisition and transmission of sexually transmitted infections. Vaginal microbiota with a small number of bacterial communities and dominated by lactobacilli (in particular Lactobacillus crispatus) are those most associated with vaginal health, whereas increased diversity seems to be associated with lower resilience to imbalances and higher susceptibility to STIs such as herpes (BV increases the risk of herpes and vice versa), papillomavirus (increased prevalence and likelihood of contracting HPV, delayed elimination, increased severity of cervical intraepithelial dysplasia), HIV (increased risk of acquisition and transmission), and other infections (gonorrhea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis).14