Breast cancer, antibiotics and gut microbiota: a losing combination

Antibiotics are commonly used among breast cancer patients, to prevent opportunistic infections for instance, or during periods of immunodeficiency. The researchers in this study show, in a mouse model of breast cancer, that antibiotics may accelerate tumor growth by inducing imbalances in the gut microbiota.

Lay public section

Find here your dedicated section

Sources

This article is based on scientific information

About this article

The gut microbiota has been linked to disease progression in several cancers. However, there is limited research detailing its influence in breast cancer. At the same time, antibiotics have an impact on the bacterial population of the gut microbiota. Antibiotic use is common among cancer patients, despite controversy surrounding the benefits. Accordingly, a study evaluating the effect of antibiotics on the gut microbiota and their impact on the clinical course of breast cancer was overdue. A recent study in a mouse model published in iSciences has filled the gap.

Accelerated tumor growth and microbiota depletion in mice receiving antibiotic treatment

Both before and after injection with breast cancer-specific tumor cells, mice were given a cocktail of antibiotics: vancomycin, neomycin, metronidazole, amphotericin, and ampicillin (VNMAA). Compared to the control group, these animals rapidly exhibited significantly accelerated tumor growth and strong depletion of the gut microbiota.

The researchers then focused on the effects of an antibiotic widely used in breast cancer patients: cephalexin. Although cephalexin had a smaller impact on the microbiota than the VNMAA cocktail, it caused a similar increase in tumor growth.

Anti-tumor role of certain gut bacteria

In the mice undergoing antibiotic treatment, metagenomics revealed a dysbiosis which, while not favorable to pathogenic bacteria, adversely affected protective bacteria. Animals treated with VNMAA and cephalexin had a lower relative abundance of bacteria thought to play an anti-tumor role: Lactobacillus reuteri, Lachnospiraceae bacterium, and Faecalibculum rodentium. By simply reintroducing the latter bacteria, the previous level of tumor growth was restored.

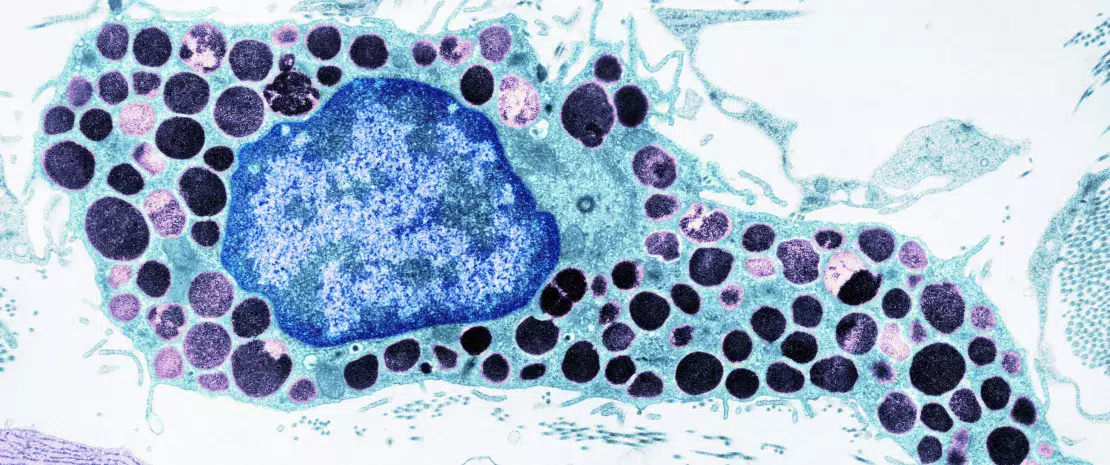

Mast cells, drivers of tumor growth in dysbiosis

Antibiotic-induced microbiota disturbances do not have a significant impact on the tumor immune microenvironment. However, they do increase the number of mast cells in the tumor stroma.

The researchers treated both control and VNMAA-treated mice with cromolyn, a mast cell stabilizer. While cromolyn inhibited tumor growth in the antibiotic-treated mice, it had no effect on the controls. These data suggest a potential role for mast cells in breast cancer progression in individuals with antibiotic-induced dysbiosis.

Even though this study was performed on a mouse model, it opens up new perspectives for the treatment of breast cancer. It is now necessary to identify what causes the increase in mast cells, what changes occur in mast cells as a result of microbiota disruption, what causes these changes, and how it causes them.